Tangerine (Sean Baker, 2015)

And a quick update

This week Sam (Borat voice) and I moved into a new apartment; a move that was supposed to be completed shortly after getting my job at Portland State in December 2022, but then, well, things got pretty gnarly in my life, and in case you missed it, society started collapsing, and so I’m only now just getting back on my feet. I haven’t posted on here in a long time, and I guess it’s finally time to make up for that.

Occasionally I’ll log in here and see my subscriber numbers move around, both up and down, and then I see the number in the corner that shows me that some of you are graciously paying me a little bit of money every month, which causes me to panic. I’ve been needing to get this place up and running to earn your trust and eyeballs now that I’m a freelancer, but I realized over the past couple of months that I needed just one last little push in my personal life to get to a place where I’d be able to freely lance. Or something like that. I really, really don’t want this blog to turn into a diary, so I will keep this part brief; but you will be hearing more from me more regularly now that I’ve settled in and my book proposal (!) is near completion.

Until then, I thought I’d share some words that came to me after watching Sean Baker’s Tangerine after hours with my new Cinema 21 family (I’m managing the cinema on Sundays now). For the back half of September, Cinema 21 is celebrating its centennial, and we are bringing Sean Baker for a screening of his breakthrough hit on the 28th. We have a bunch of other special screenings you should check out over that timeframe, including an opening night celebration with a few unannounced surprises; tickets to which you can purchase here. That’s some of what I’ve been up to over the past two months, which also included two conference presentations that allowed me to work out some of my key ideas for my book proposal. I hope to tell you more about that soon.

Corbin and I also concluded our Digital Frontiers series over at The Pacific Northwest Insurance Corporation Moviefilm Podcast, and I’m particularly proud of our final episode on Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia for many reasons, including the intro bit which you can hear above. It was a chance for me to remember these episodes can be more than just two microphones picking up blabbering for two hours once a week.

Anyway, more soon, including news about forthcoming classes at Cinejourneys, one of which will be a timely look back at Weimar Cinema. For no reason. Yknow, very little we could learn from that moment right now.

Tangerine (dir. Sean Baker, 2014)

Man, I really regret waiting this long to watch this. I saw the clips, read the articles, and felt like I kind of got the gist; not because I had no interest in the film or its subject matter, but rather due to what I had been up to in my work over the past decade. I have been teaching a post-cinema/digital cinema course since 2017, which has required me to stay "up" on anything like this with an interesting production history or formal structure, regardless of the film's content or my own interest. At some point, you have a giant-ass list of movies that never gets smaller, since you stupidly chose to research an unfolding topic rather than a historical one. So I put this into the "someday" pile, thinking I had understood its relationship to the unfolding post-cinematic academic project well enough to go on without it.

This view was compounded by watching the response to The Florida Project, which I followed online and also sat in the room half watching with my wife when it hit streaming. By this point I really felt like I understood what this whole Sean Baker thing was: a return to an American neorealist aesthetic following the whole mumblecore thing (ugh), a necessary subversion of that genre's twee millennial cringe with transgression and Real Shit, supported by a new wave of filmmakers who grew up online rather than with the VCR. Now, if you've gone to grad school in the humanities, you're trained from day one to always be skeptical of anything claiming to be Real in opposition to some vague (and usually undefined) Not Real. "Real" is a construction--not only aesthetically (within film history: pulling from the Italians in the 1940s to the French direct cinema/verité movements, or American indies from Cassavetes to the 90s festival wunderkinds, always existing in opposition to the normative Hollywood system of the time) but also ideologically (as a marketing gimmick that makes your commodity more "Real" than those "Fake" ones, belying the fact they are both fake, because they all being sold for the same reason!).

From what I've seen, The Florida Project aggressively fails at both these tests: that transgression subdued and commodified for the emerging A24 crowd, which transforms realism's purpose away from critique to a marketing tool that can be used to paper over a classic Hollywood story in line with the dominant ideology of the time, in which Hard Work and Perseverance are offered as ways out of the system, excusing its contradictions. My surprise at the madcap, slapstick turn midway through Anora, then, was a realization that I had gotten this all wrong. Doubly so when I watched this. I had even shown clips from Tangerine in class while teaching about digital cinematography, although purely as a formal exercise. But to be honest, the more I sat through this film last night, the more I realized I needed to wait for Anora to really get what Baker's whole deal is.

I think Tangerine works best if we take the entire thing--narrative, production history, critical response--as a metaphor for making digital cinema in our era of ubiquitous screens and smartphone cameras. Book it as a double bill with Soderbergh's Che, a movie that uses the revolutionary history of Cuban armed struggle against a colonial power as a narrative exercise for Sodey to suggest he's doing something similar inside Hollywood, armed with a RED camera, flaunting a middle finger to the Harvey Weinstens of the world. Tangerine practices this same move, but instead of revolutionary history, it uses transgression, equivalence, and illegality as its devices. Note how its characters are not merely "at the margins" in society but also literally occupying spaces this way within the diegesis of the film: Razmik uses his cab to pick up trans sex workers, each of whom know which block you should and shouldn't go down, our comedic leading sex worker protagonists Sin-Dee and Alexandra are either fresh out of prison or doing business in the lobbies of donut shops.

Are these narrative attempts to work within a hostile system, subjecting our protagonists to the margins of the law, navigable only through transgression...not like shooting a movie on an iPhone without a proper permit? Saying Fuck You to doing it "The Right Way," breaking both cultural and legal norms to get what you need? If Hollywood is one law then so is the state's view of sex work, and also gender itself. The breaking of each of these three laws is not posed by the film as merely "fun" or even ethical (Baker is wisely utterly disinterested in a kind of feel good liberal moralism that gives us crap like Emilia Perez). It is instead posed as necessary, but also liberatory. Baker made his movie and he made it by transgressing, because the rules need to be broken. That is a victory, as was giving jobs to his two formerly non-professional leads; but Marvel still won the decade, and now the Republicans are trying to legislate trans people out of existence. But that's what makes this film feel so alive here in 2025, coming to us from a moment of possibility when things didn't feel quite so dire. I wonder what it would look like to keep this spirit alive not just when we think about cinema but also the lives of the very real people this film depicts for us on screens that don't typically feature them.

Back to the film. By now, Baker knows how to block, stage, and shoot a scene backed by the resources and trust of independent financiers, indie studios, and smaller distributors. Note the way Anora's madcap sequences in the back half of the film use longer takes with his actors moving their bodies in space, interacting with their physical environment in ways that Marvel Green Screen Hegemony and Netflix austerity pushed out of regular practice on sets. In Anora, Baker understands that frenetic energy can emerge from longer takes if his actors conjure it, if he holds his camera with shaking hands, or if his mise-en-scène and soundtrack become props of their own to throw around the room and smash at will. When he breaks up a scene by cutting quickly, it's usually to map the space over a call on speakerphone between two locations, cross-cutting while two ends of a phone call scream at each other in attempts to locate either side to no avail. It works so well in Anora, because it seems to understand that the best way to manipulate Hollywood continuity is not just to throw it away but to control your viewer's access to its rules imposed by the demands of narrative and intended affect. When we stay in a longer shot with fewer cuts, we feel stuck in a room; when we are frantically cutting back and forth between two people across town yelling into their phones, we are just as confused as the characters, searching for some kind of unity to make the whole thing fall into place.

This is one of the reasons why Anora was compared to the energy that the Safdies deployed so effectively before their split: something like a new American style seems to be emerging in response to the hell world of apps and texts from your bank telling you you're out of money, but one literate in Classical Hollywood form that Marvel and streaming has pushed off our screens over the past decade.

Not so for Tangerine. In the film's first half, Baker is cutting like Dziga Vertov on his first dose of adderall. I regret to say I wasn't really a fan, and compared to the controlled chaos of Anora it felt amateurish. But I think there are two ways to read this. For one, it's a director starting to discover his superpowers, while at the same time not yet knowing how to control the electricity flowing from their fingers. I have taken to calling this Magnolia syndrome after PTA's ambitious but irritating first encounter with a big pile of money. When Baker does this to stitch together the various threads at the beginning of this movie, it feels as if he can see the final product in his head, understanding that he wants that chaos to burst through the screen at the viewer, but lacks the resources both financial and technical to really pull it off. I'd imagine part of this comes from using on-the-fly performances from his non-professional performers. You can imagine him on set, holding his phone camera in a tiny rig, rolling for thirty minutes with new ideas spontaneously coming one after the other. This mode of digital capture has long been part of the digital revolution, where directors can let scenes play out forty different ways, later stitching the takes together into one "perfect" take made up of so many different line reads. If you have the resources of David Fincher or Alfonso Cuarón, you can stitch these into even seemingly unbroken long takes; but here I can imagine Baker just trying shit out and tossing it all together in Final Cut like a proof of concept for the real thing. Except this is the real thing.

But on the other hand, maybe that's the point. A more generous reading would be that this type of rapid editing is an inevitable product of a mode of film production that uses new, cheap consumer technology, emerging--and this is important--at the exact moment of social media's ascendancy to power. Today, our aesthetic experience is no longer conditioned by cinematic or televisual time. We live instead in the world of the eternally updating feed. Of course our images need to move fast to adequately reflect this shift, where reality itself is increasingly given to us via montage when we swipe up on our feed of course. Baker shooting all these takes and then throwing them into a non-linear editing program on a laptop later that afternoon wasn't then some groundbreaking idea, it was just what was possible at that moment of technological convergence. It also puts the film in conversation with other digital film techniques that have been emerging over the past few decades, from the handheld DV of the Dogme movement to the indie horror wave that emerged out of the YouTube short and creepypasta meme scene. But that doesn't really make Tangerine all that interesting. Putting these early scenes together like this feels more to me like a filmmaker discovering the same things every generation of filmmakers discovers as they attempt to break into an industry with powerful gatekeepers, armed with whatever new technological form was emergent at the time, be it 16mm film or the VCR tape.

About halfway through Tangerine, you start to see the Baker we now know start to show his face. The film's eventual climax--where poor Razmik's mother in law drags his entire family to the donut shop, in which Sin-Dee and Alex's plotline is also converging (Bordwell's double plot line!)--might have been the place to really put that rapid editing to use. But the film smartly gives it up about halfway through, finally allowing us to settle into its world, as unfolding actions on screen finally, mercifully, play out from start to finish. This shift isn't arbitrary, either. The moment Tangerine finally slows down comes (heh) during an incredible long take depicting a(n illegal) sexual encounter taking place in the privacy of Razmik's Taxi, going through a drive-through car wash, the act unfolding just below the screen while the soap sensually streams down the windshield shot continuously from the backseat like a view we shouldn't have access to, but do, because we all have cameras in our pockets now. I was blown away by this shot (heh x2), and it was at that moment I realized that this movie is almost one big sizzle reel for Baker to flaunt to an otherwise hostile industry, saying Look at this shit. Look at what I can do. Give me some money!

There is textual evidence for this "transactional" reading of the film, too. Baker's script understands that everything that happens in the film's diegesis--and by extension the decaying late capitalist social system we are all stuck in where we watch his movie--is also nothing more than a transaction. Everyone is always working; our trans sex worker protagonists are not just always looking for money, their social structure is entirely constructed by necessary transactional relationships that allow them to navigate their marginal relation to the "proper" and "legal" social totality that doesn't have a place for them as they are. Is this not what we all do, every day, regardless of the particulars of our subjective particularities? The film is smart about this. It's not just about "being trans" or "being a sex worker," both of which would make for great films on their own; it's about abstracting the particularities of what reads to normative American hegemonic culture as transgression in order to tell us that we are all stuck in this system, this shit is imposing itself on all of us.

Take for instance the aforementioned climax of the film, where Razmik leaves his family's Christmas Eve party under the guise of "work" to see Alexandra. By this point it seems clear he isn't just looking to get off; he legitimately desires her, and wants to be with her. He lies to his family with the excuse he needs to get more work done; but let's be honest: what he left to do was work. Everyone is working here; Alexandra performing at the club, Razmik is paid to know how to navigate the streets of Los Angeles, even Sin-Dee, violently dragging around another sex worker she later has an intimate encounter with while getting high--is navigating this economic structure imposed on all of them that equates mobility with labor. The whole thing breaks down at the end in classic screwball comedy fashion, but what would have happened had it all gone right? Razmik would likely have paid Alexandra for the emotional encounter at her show, either by his ticket at the door or something else. Nobody shows up to her performance, but even if they did, we discover that Alexandra paid the club to sing rather than the other way around. It's not just these two: the film's dialogue is riddled with transactional language. The woman working at the Donut Shop tries to break up the fight by shouting "Stop yelling! This is a BUSINESS!" Razmik coaxes information about Alexandra's location from another sex worker coded like an order at a fast food restaurant (the final bit of information costs "a cheeseburger and fries"). This is just how you do business in the world of sex work, but it's also increasingly the way all social interactions function. Everything is commodified, from intimacy to selling your labor power itself. Which is what Baker is doing shooting this film on an iPhone! Selling his labor power in a transgressive manner! He scrounged up a tiny bit of money and bought anamorphic lenses to put on a bunch of consumer smartphones, and dammit, it's a REAL film even if "You" don't think it is.

Something that pop criticism of capitalism has not fully grasped in this turn back to Marx since 2008 is that capitalism isn't just "when there is money" or "The Economy," but is rather an economic system that reduces every social appearance to economic value through a system of equivalence. Marx tells us that money in a capitalist economy functions as the medium to account for differences by reducing them to abstract equivalences. It organizes the structure imposed on all of our social lives by reducing what we ontologically experience to an abstraction of value that can be expressed by a number. Tangerine is a film then that not only shows us what this system feels like after it has run out of things to plug into the equivalence machine, forcing people to live at these margins. It also gives us a story about searching for a Real within that system that requires transgressive actions like using your employer's car to seek human contact society has rendered illegal, or using an iPhone to make a movie that plays on the same screen as the big studio pictures done the "Right Way." All of this is the same, and it calls into question the division of Real and False, Right Way and Wrong Way within this system of equivalence, as if to break it apart from the inside out.

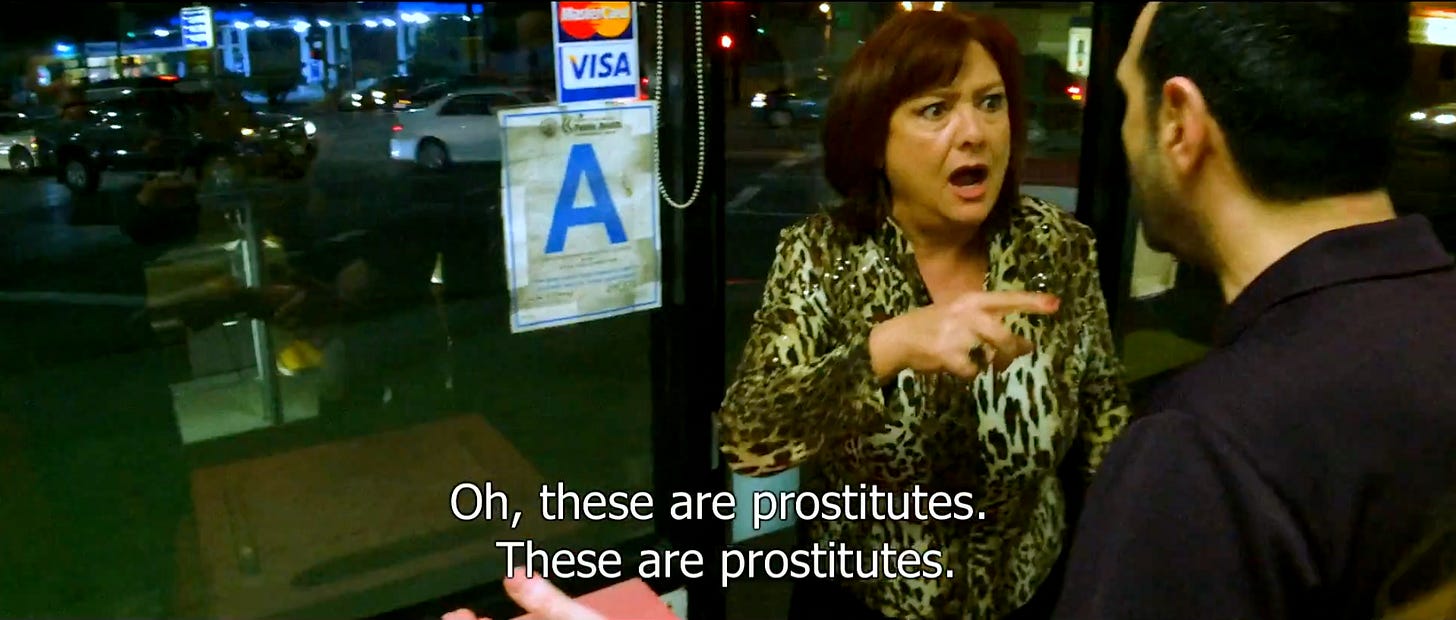

In the climax of the film, when Razmik's Armenian mother in law catches him at the Donut Shop talking to Alexandra, she recoils in horror when she discovers they are....gasp....not only "prostitutes," but MEN!!!!!!! Razmik rolls his eyes and trying to calm her down, tells her "No, these are regular people!" That the film also formalizes this appeal to a Real that is not outside the system but within it regardless, down to the technology it was shot on, makes it one of the most compelling films of the decade. I just wish he would have cooled it with the jump cuts in the first half.