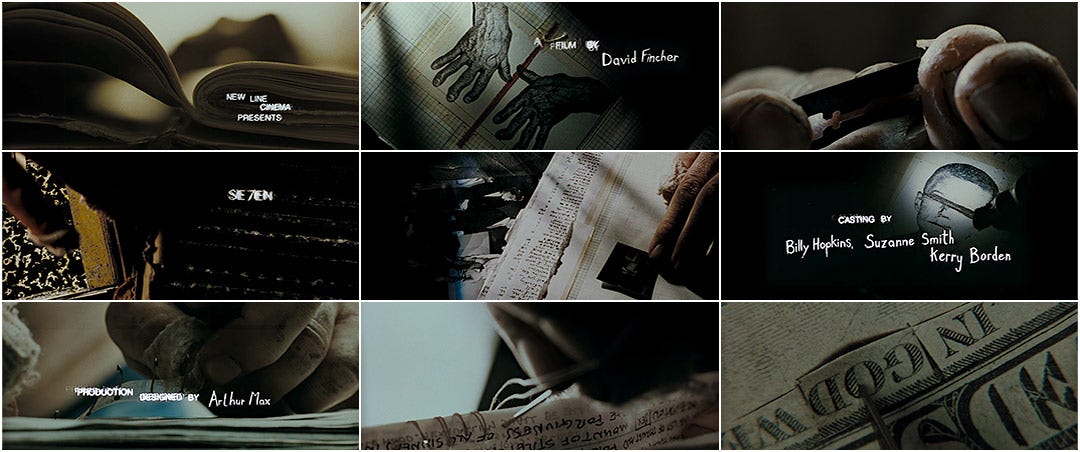

Se7en (David Fincher, 1995)

A warning from the high, End of History 90s

I had a chance to see a 30th-anniversary 35mm screening of Se7en over the weekend and was reminded how great the movie truly is. In my post-credits daze, crawling out of the theater, I overheard a few shocked reactions and exhortations of disapproval, which got me thinking. Se7en is, ultimately, a widely misunderstood film; one problem is that many negative readings are the result of mistakenly treating the film as a work of vulgar auteurism in such a way that one misses the trick the script is pulling on its viewer. Why is this? It’s because David Fincher's rise to auteurdom came at a time in which the Hollywood mode of production had shifted away from its high-Classical period of vertical integration, with its strict division of labor (directors being assigned scripts), and towards one where what it meant to be an auteur was for directors to have a deep hand in the crafting of their filmic narratives (think Coppola hiring Mario Puzo to write The Godfather) or simply wrote them themselves following the run-and-gun 1980s American independent years (Tarantino).

Se7en is of minor interest as a chapter in Fincher's filmography, a preview of the concerns he would interrogate much more skillfully later in his career. It is clearly not the work of a master artist yet; it oscillates formally between styles that feel more like attempts at homage than a distinct authorial mode. The action scenes are thrilling, but the camera moves so quickly it can be hard to make out what is going on (see the chase through the apartment complex), shot as they were in handheld 35mm. It doesn't seem as if the film is trying to present you an overwhelming sensory affect here as much as it didn't quite know how to skillfully speed up the pace and tempo without losing the careful procedural energy it has in the slower scenes, which would become a key signature of Fincher's in his post-Zodiac work.

Those scenes also present a bit of a problem, coming as they are right on the cusp of the end of print culture. Fincher's rise to become one of our two greatest auteurs of digital proceduralism, a role he shares with Steven Soderbergh, could only happen after the invention of the RED digital camera and the proliferation of non-linear editing systems that gave each the total control their obsessive styles demand. At one point in the narrative, Freeman's Detective Somerset has to go to the library to receive information to propel the narrative forward (in a key moment, our protagonists pay off an FBI informant who has access to some secret database where the Feds are keeping track of what books everyone checks out from the library, a fantastical invention that surely seemed to serve as a creative way to get from point A to point B but one that, it turns out, was actually a warning of what was waiting for us in the smartphone era!). All of which is to say nothing about the general sense that Fincher takes himself Very Seriously as one of America's great 90s music video pomo directors, an eye-rolling work of Male Genius that we supposedly grew out of (but lets be honest with ourselves, ended in an era with a spoiled party kid president who destroyed the middle east, a spirit cinematically embodied in McKay's Step Brothers).

(you can almost see Fincher and designer Kyle Cooper in music-video mode in the film’s iconic opening credits, trying to invent Final Cut with glue and scissors just before it existed)

But Se7en's true genius is Andrew Kevin Walker's script; for my money the single best of the decade, one which we might even be able to argue is playing a joke on Fincher himself. But it’s also, I think, playing a joke on many of its disturbed viewers who misunderstand what the film is actually up to. It is a script that fundamentally understands Hollywood storytelling in an era of empty genre pastiche, especially one in which the "neo-noir" became the privileged site of detached, ironic postmodern play. This is a movie that takes the absurdity of its premise deeply seriously, not in an edgelord, Reddit way--"man wouldn't it be FUCKED UP if (describes the torture contraption Leland Orser's character uses to horrifyingly perform the killer's "Lust" murder)?!?!"--but rather to ask, What if that happened? What if things like that weren't just Epic thought experiments in the spectacle for Dumb Guys, what if there were actually people who did shit like that? It seems harder to laugh at that suggestion after reading the kinds of things Gen-Z neo-nazi posters talk about in their group chats! It's a warning from a more innocent time, one that was misread by progressive pomo liberals as playing with moral panic, but one that comes not from a reactionary place (what kind of judgements does the film encourage its viewers to make about its victims or the causes of crime?) but rather an awareness of what was waiting just around the corner during the high, End of History triumphalism of the early 1990s. This is a film that actually does what Fight Club defenders claim that film is doing, and that it refuses to play by the rules its critics wish it did is emblematic of the film’s project of critique.

In this way, it's ironic people treat the film as a kind of 90s/00s bro, edgelord object. Much of this comes from our short historical memory in the digital era, as well as the need for dominant culture to make fun of what was previously popular by somehow blaming all the current enemies of What's Cool for the oppressive insistence on What Used To Be Cool they take as their fault, even though these two things are hardly ever related. We have constructed a false memory of the decade: 90's ironic pomo culture was sincerely insincere, dominantly liberal. It was young and hip and Cool, detached, Smarter than anyone trying to slow things down and tell people that History might have other plans for everyone. What do you mean take things seriously, are you a fucking square? But once the murders start to hit, Freeman's weather-worn detective Somerset--a Black institutionalist who seems to operate both within and without the urban landscape without becoming an avatar for any dominant generational ethos--is the only one who understands what is happening and takes it seriously from the start. R. Lee Ermey's police captain is desensitized to the whole thing--he can barely keep track of new victims from the other, unrelated victims he manages at the head of a sprawling, inhuman bureaucracy. Somerset’s first place to go is the library, reading old shit like Dante while the rest of the police on the scene play cards and wait for someone to burst into the public space to announce their crime and force them to do their job (the film repeatedly reminds us this is what cops actually do). And then there is Brad Pitt's Detective Mills, who has to order Cliffnotes because he doesn't read; what is he, some kind of loser?

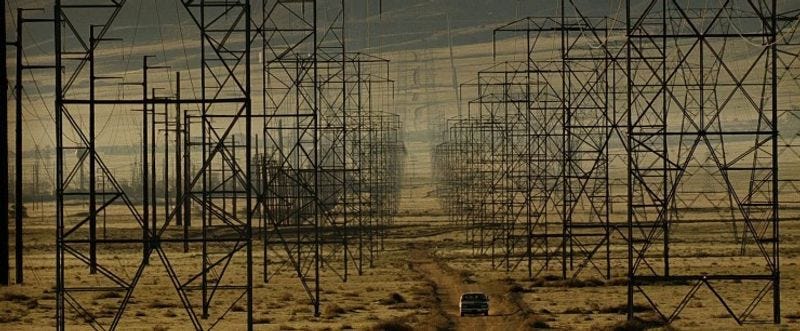

Freeman's Somerset is repeatedly warning everyone he encounters that they need to grow up and start taking things more seriously. Importantly, this isn't out of knee jerk reaction but a place of serious, sober concern for those around him and the society he deeply cares about. He doesn't want to do this job anymore; an instance of the one-last-job motif that popped up again and again especially in neo-noir pastiches beginning in the 1970s which was there meant to signify the pastness of prior media objects being pulled into the present to be mined for one last run through the Content Wringer, but here signifies History's desire to be done and over with before realizing that everyone seemed to miss the lesson it was trying to warn us about in the first place, and so maybe they are going to have to stick around a while longer (Freeman’s last line in the film, “(I’ll be) around”). Paltrow's character is the polar opposite of a 1940s noir femme fatale, she's just a normal person who wanted a normal life, being dragged into some personal psychodrama by her maniac husband. One reading has suggested the film thinks she is somehow stupid; I think she, along with Freeman's Detective Somerset, are the only sane people in the entire script. It is a story in which America is caught obsessed with its own reflection at the End of History, full of an ironic postmodern detachment that is ultimately just a mask for a naive narcissistic sincerity that (PROVED ITSELF!) completely ill-equipped for handling a world where History was waiting again around the corner, either in the form of Kevin Spacey's murder turning himself in or Trump winning the 2016 presidential election.

In fact, Pitt's Mills is the too-cool, Above It All critic of this movie, rolling his eyes at everything he encounters (that he would have known about had he done the reading). At some point the work it takes to keep up that act becomes the new definition of sincerity itself, a desire to blind oneself from what's uncomfortable for fear of being forced to act in a world that demands moral compromise without easy solutions. I'm reminded here of those legitimate heroes who spend time researching neo-nazi internet communities to try and warn us about what they are up to while most normies would get one whiff of anything remotely disagreeable and say "what a FREAK!" as if that is an answer for how to stop them. In Se7en, Pitt's Mills assumed he won the culture game, he assumed he was the protagonist of the twentieth century, achieving the "hard-fought" job out of the Academy only to land in an apartment underneath the subway tracks, but one that would allow him to prove himself one day with all the markers of Having Made It His Way, because what's really important is that He made it, above it all. Meanwhile Detective Somerset is trying to warn Mills about what's waiting around the corner; he’s not prepared to see what’s inside the box.

By the end of the film, in the car on the way to the final reveal, Pitt's Mills face to face with the film's representation of the Real finally captured in the back seat, you would think he would be able to finally face what's coming. Instead he just mocks it spittingly, "You're a movie of the week! You're....you're a fuckin' T-shirt!" How many people do you know like this who didn't take the events of the early 2010s--no, screw it, even the early 2020s--seriously enough to do something about it beyond complain? And what the film presents as a counter to this--masterfully worked out in the script in the film's best sequence, where Somerset and Mills debrief over food shortly before the film's climax--is two worldviews sparring it out, the film clearly taking the side not of reaction but of a true sincerity, one that doesn't hide in silly genre cliches or pop-cultural signifiers meant to convince the utterer of their superiority over what's uncomfortable instead with a sober realization that this stuff is out there in the world, demanding of us not a retreat into reaction or the detached stupor on Pitt's face as he is driven off to the funny farm, but for us to wake up tomorrow, roll our sleeves, and get back to work.

Great essay Matt! I'm a huge fan of this film, think you are spot on