On Marxism and "Religion": A Project Proposal

Introducing this long-festering idea to you now so you know what you signed up for

I’m still in the process of figuring out what I want this blog to be (do you even call these blogs anymore?). I want to be able to post some analyses of contemporary events from a theoretical perspective, something I’ve been doing in short form on Twitter for too long to exhortations that I need to put my insights (or lack thereof) into a more “proper” form. On the one hand, I enjoy the tweet format, and think brevity can help sharpen ideas and fit into the tempo of contemporary life more than longform writing, which takes time, and which few of us get paid to fill with Wikipedia rabbit holes. But on the other, I’ve definitely left career opportunities on the table (I have had writers block since grad school gave me an anxiety disorder) and missed some golden years of actually getting paid for intellectual work when the internet was cool. So that’s part of what I’m trying to fix here.

Most of you have recently subscribed as a result of my last post, which consisted mostly of my immediate reaction to the results of the election filtered through some of the theoretical and historical frameworks I have been exploring over the past few years. That puts a bit of pressure on me to define exactly what this space is going to be, and so today (I’m aiming for one main post a week with some shorter capsules as they come) will be an attempt to introduce some other ideas I have wanted to explore in recent years as a kind of exposure of my hand. Some of you are probably going to be like what the heck, this isn’t what I signed up for! but unfortunately you are now legally obliged to read each article within ten minutes of their posting and also pay for the highest possible “optional” subscription tier so that I can become rich and famous. I don’t make the rules!

More realistically, I want to assure you that I see my proposed triptych of “Media/Marx/Culture” as the ongoing operative framework of this blog, so if this post scares you, don’t worry! I’ll be writing about movies and politics and music and internet culture as well. So in other words, I hope you stick with me as I explore where this whole thing is going to go. I promise to try and keep it interesting, and newly freed from the requirements of boring academic writing I’ve never been able to master: a mixture of careful argumentative prose with bits, jokes, and the internet speak that is now a widespread vernacular here to stay no matter what journal editors think. So without further ado, onto the Real Stuff.

I am a Marxist and an Atheist. However, I am also deeply interested in what we typically call “Religion,” and think it is something we don’t talk about enough in the way I want to talk about it. There has been plenty of discourse about the Christian Right over the years, and this is not really what I am interested in here (although I do have my own account of what, exactly, that whole thing is). This will require a little bit of personal narrative that I typically don’t want to subject you to on this blog moving forward, so I will try and keep it brief.

For those of you who don’t know me personally, I, like many of you reading this blog and set between the ages of, lets say, 30-100, was raised in an Evangelical Christian household during the 90s and early ‘00s. I do not have anything resembling a remarkable childhood: we were a white middle class suburban family living in the Pacific Northwest. It was the End of History, a moment of triumph for what we now call neoliberalism, but also one in which the conservatism of Reagan’s America produced a society where Christianity returned to its centrality for the reproduction of (certain) American institutions in the wake of the revolutionary ‘60s. The depoliticization of the Boomers, the reinscription of capitalism’s need to reproduce the labor force for the neoliberal cycle of accumulation after the end of industrialization. The Big Chill.

I’m a Millennial born precisely in the split between “old millennials” (1980-1986) and the younger group that make up the rear. My formative years were spent on early Web 2.0 forums like Something Awful, but I also grew up with a green screen DOS computer upstairs during the early 90s and learned about the Dewey Decimal System in school. I started teaching college at the precise moment where younger millennials started to be replaced in the classroom by Gen Z. I vividly remember every minute of 9/11 (it was our school’s photo day, I eventually want to track down this book as I think it is a profound collection of the indexical experience of the first true Event of the twenty-first century). I had high school friends who died in Iraq. I couldn’t get a job in the Great Recession. I first felt “old” when Gangnam Style became a craze on the internet; this was also the moment I first learned about The Libs and what would become the Cringe internet as normies started to log on at the same time in the early ‘10s and invade spaces where those of us who had learned how to post on Encyclopedia Dramatica had been simmering in by ourselves for years.

Most unique to my story, I guess, is that I dropped out of college in 2006 to play music in a band—a Christian band more precisely—and spent the late 2000s touring and releasing albums on Facedown Records. In other words, I grew up in my own Evangelical millennial bildungsroman, one that so many in my generation experienced as we were set out into the world, only to be met with the unexpected crises of 9/11, Iraq, and the 2008 market crash. As others have argued, these events resulted in a widespread turning away from organized Christianity and religion in my generation through the rise of the so-called “Nones.”

In my particular case, I started taking online classes at community college while we were touring and (this is embarrassing) enrolled in a philosophy class that blew my mind, and released a concept record about my attempt to rebuild my rapidly declining faith as a direct response. This record just so happened to be matched in its conceptual pretense with a sonic turn towards experimentation that was not met well with our label’s fanbase, mostly comprised of youth group Metalcore kids wearing skin-tight shirts adorned with splatter designs on the lower hip depicting teddy bears getting murdered in Fruit Loops colors. Long story short, I lost faith as a twin result of the band falling apart and the academic research I was undertaking (and of course, due in no small part to the initial rumblings of the Tea Party either). I re-enrolled at a four-year institution at the same time that Occupy was taking off, and BAM, I had a new Meaning located in what we now call the “Millennial Left.” I had no idea what I was going to do for a living, so I decided to apply to grad school, as the classroom was something I was “good” at after the band ceased to be my primary source of income, and the rest is history.

In 2020 my faith in the left was tested, however. Like I said in my last post, I was never under some illusion that Bernie Sanders’ warmed-over nostalgic social democracy was some kind of salve to stave off imperial decline. By this point I was pretty deep into a scholarly turn towards Marxist accounts of history, and the 2016 election was a bit of a kick in the ass towards the gut feeling that what was really underway was a crisis of capitalism’s neoliberal period of US-led global hegemony that materially broke in 2008, and only became visible later to surprised elites as a result of the twin-assault of a Dang Cheeto in the White House and the United Kingdom’s exit from the single market on the continent. In retrospect, what had really happened over the past decade was that I had replaced my religious foundation with a faith in the historical materialist project, a New God.

ahh fuck no NO NO! NOT LIKE THAT!!! I’M STILL ON THE TEAM!!!

I wasn’t interpreting Sanders’ runs as any kind of evidence that the dialectic was about to resolve itself or anything. But they provided me with a sense of a newfound, unalienated Meaning that got me out of bed each morning because it felt like there was something we were all doing. When the DNC coordinated to push a rising Bernie out of the primary process to ensure that their project of Keeping Things Normal under the protection of the liberal wing of Capital happened, I was caught off guard. Then we all got locked inside! I distinctly remember watching the final season of The Sopranos during the pandemic as my latest tactic to fill long days of repetition and feeling this profound sense of dread and despair—I knew that the show ended with Tony’s apparent death, but the episodes leading up to it, when watched with that in mind, felt like a train slowly applying the brakes as it enters Hell’s Station, last stop on the line.

I weirdly didn’t emerge from this funk until Trump won last week (although I have a lot going on personally, too), which led to my initial confusion, but which now seems clear to be a fucked up kind of comfort that History is moving again. I suppose this is why Mark Fisher always resounded with me even though I later came to fundamentally disagree with his total doomerism, which was ungrounded in the historical materialist account of change and stuck in late 90’s Theory Land (completely understandable for the moment in which he was actively writing). But it also took me a lot of thinking and reading to get to this point, thinking which truly only really began in earnest after I finished my dissertation and cast off the conceptual frameworks I felt a need to adhere to for disciplinary legibility and career branding. I was cleaning out my Amazon lists the other day and remembered when I’d just throw anything on there that was remotely related to my dissertation project; now the thought of reading another book on neoliberalism and financialization makes me want to claw my eyes out with a rusty spoon. GET ON WITH IT MATT! Ok sorry.

The Conceptual Shift

Around this time David Graeber and David Wengrow published The Dawn of Everything, a book that uses both anthropological (Graeber) and archaeological (Wengrow) insights to attack dominant narratives about the rise of civilization and the nature by which we feel “stuck” in sclerotic institutions resistant to change and the flourishing of freedom and The Good Life. I was already familiar with Graeber’s work, as his book on debt was useful in my dissertation, but I was also aware that as a radical anarchist anthropologist, he was prone to making somewhat outlandish claims. I always sort of treated these as necessary thought experiments, kind of like what happened when I read Foucault: the so-called “truth” of what they were saying didn’t matter as much as the kind of thinking the claims made possible, which train you as a reader to conceive of the world in radical and necessary new ways. For example: in Debt, Graeber claims that money did not emerge in history as this Big Bad material abstraction that paved the way for oppression and greed; rather, debt came first, which facilitated the need for a unit of economic measurement, as the gift economies of hunter gatherers started to give way to more low-trust exchanges built around barter, when bands of people began to meet others outside their tribe. While this is a topic of longstanding debate between economists, many leftists find this theory unsatisfying, as one can see most clearly in the ongoing debates between the neochartalists (MMT) and Marxists. But I could really give a shit about all that stuff anymore, and I think Graeber is interesting to read precisely because I don’t really trust him with any big historical claims, but find immense value in his epistemological experimentation and political commitments.

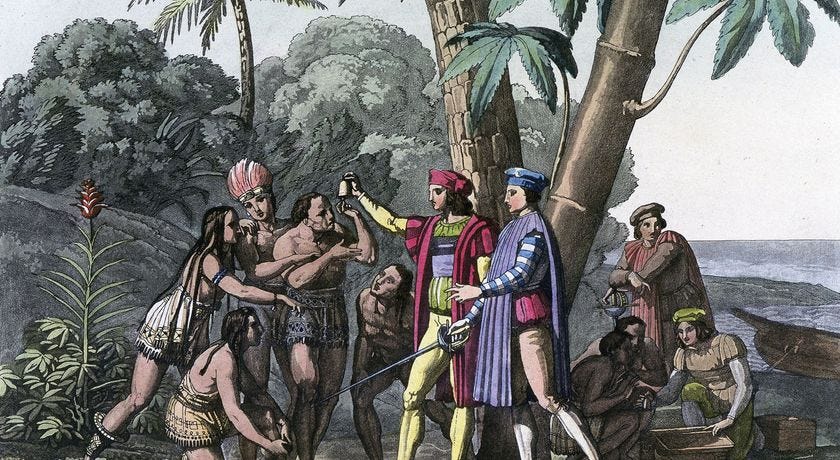

The Dawn of Everything is no exception. Graeber and Wengrow claim, for instance, that the entire European Enlightenment came as a result of European intellectuals hearing from indigenous American thinkers that they had a better way of organizing societies, and were shocked over not only the violence but also the mere rigidity of Western Modernity being imposed on them during the Columbian Exchange. In other words, we have the concept of Freedom now because the indigenous Americans planted the original seeds that grew the riches of our Emersonian Minds.

This is a mistake that only an anthropologist would make. James C. Scott once wrote a really fascinating book called Seeing Like A State, and while I think he’s mostly full of shit (and once helped the CIA spy on the left!), his central framing concept shows how useful Anthropology can be as a method: States “see” things differently than individuals or even private institutions. In this account, what the state “sees” is an America made up of a collection of random people who engage in economic exchange which can be directed by institutions and organized into discrete structures that State Power will oversee, and so on (whereas even “American ideology” or whatever that you carry around in your head would “see” a vague social contract between families and identity groups that guides individuals to act in a certain way). One “sees” things differently on top than from below, in other words.

Of course it would make sense to Graeber to argue that two societies with radically different norms and structures, when forced into an encounter, would express confusion as to why the other operated in a manner they found inefficient and contradictory according to the logics of their own. That’s what he’s trained to “see” as an anthropologist. But this is a banal observation. Graeber’s claim that the European theft of Indigenous Knowledge is the source of ideas we take to be our own feels to me more like chasing a trend that was happening in the academy at the time, obsessed with the politics of Finding Other Things To Talk About To Get One Of The Few Jobs Left And Use This To Also Solve Our Diversity Crisis (at many of the POC candidates’ expenses!). Of course Europeans stole Indigenous Knowledge. They stole all their stuff, and in the process thought they were primitives and incapable of abstract thought! As every political theorist worth a grain of salt would tell you, the emergence of the liberal subject—the “individual—in modernity arose as an outcome of the development of capitalist economies and their need to expand markets and private ownership over land for individual economic subjects as the middle managers were in the process of “beheading” the feudal king, so to speak. Its origin is not in some Truth that should be fetishized as a noble savage trope, it is the founding myth of Western modernity and the key that holds this entire vibrating and cracking thing together in the first place. But it also provides us the possibility to imagine freedom from natural constraints! It’s dialectical! Which of course melts anarchists like water on the Wicked Witch but I need to stop complaining about them.

Marxism

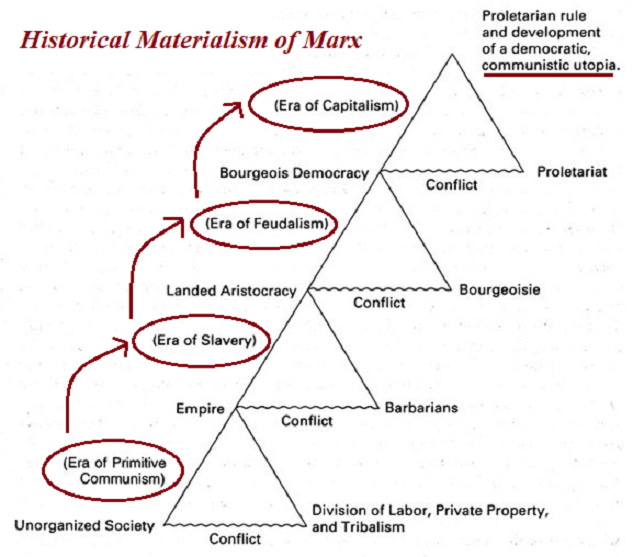

But on the other hand, Graeber and Wengrow do have an important insight (one that Wengrow backs up with actual fieldwork that Graeber began to eschew more and more of as he became somewhat of a leftist public intellectual). Traditional accounts of the development of civilization—even Marxist accounts—typically look something like this: humanity as such began in an ancient period lasting tens of thousands of years, “organized” (they weren’t really organized in any conceivable way, but you know what I mean) into so-called “primitive communism,” in which hunter-gatherers in tribal or “band” societies mostly took care of themselves and shared resources, engaged in primitive warfare and disorganized exchange, and moved around so much that no real need for lasting institutions ever took hold.

At some point, someone started planting seeds in the ground and the Neolithic Revolution began, in which we started to settle into more permanent and sedentary habitations, growing our own food rather than foraging. But this creates a problem. For the first time in history, a surplus emerges: what do you do with the extra grain you produce and save for the winter? Who decides how much Anat gets to eat? Who keeps it (me!)? Enter: the Big Bad State (for anarchists,) or Politics as such (for mostly everyone else).

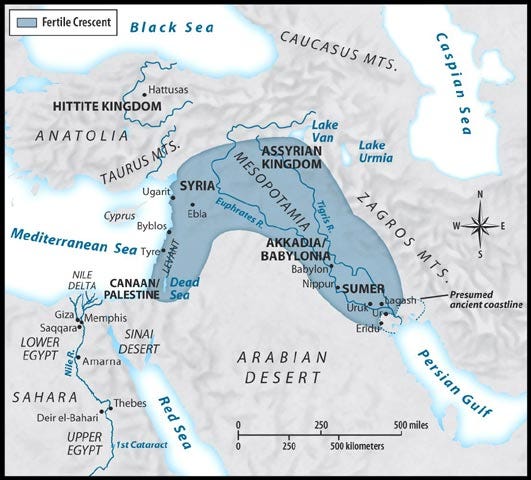

This period of civilization lasts a while with its own set of crises, and eventually scales up to the development of the City State (Sumer, Ancient Greece, etc), which eventually turn into Empires (Mesopotamia, Egypt, Hellenistic Greece, Rome, the Mongols, and so on). However, after a period of time, these Empires begin to stretch too far and capture too many subjects to adequately manage themselves with the technological limitations of their historical periods and the contradictions of their political economic orders. At this point in history, Empires are for the most part still organized by a mode of production in which slaves are imported to do most of the labor, and this creates problems during expansion as you acquire more and more land. Rome starts to collapse for a number of overdetermined reasons, and hey would you look at that this new cult that had been spreading in this strange messianic group of Jews gathers enough followers that the Roman Emperor Constantine decides to adopt said cult as the official state religion in an attempt to hold a collapsing society together. Christianity now enters the world stage.

At this point, the remaining Roman aristocrats become priests and Roman society begins to Christianize. What was once a radically disorganized, revolutionary universalist project for self-organizing small groups under an Empire no longer able to provide basic services for its subjects becomes a new way of organizing society as such (Christianity’s universalism is is also convenient if you want to convince a bunch of otherwise free individuals to do work for you rather than simply abducting them as slaves, but that’s another part of the story). The wealthy Romans that were spread out across Europe, in concert with converted “Barbarian” tribes that had slowly been integrating into Roman political structures following centuries of warfare, eventually start to synthesize into what would become a vague “feudal” structure across the European continent, with Lords and aristocrats and Kings and what have you. This is really the foundation of the church as we know it. Perry Anderson has a great bit in Passages From Antiquity to Feudalism where he essentially says Haven’t you always wondered why Catholic Bishops and Cardinals wear such funny clothes? It’s because they were the Roman elite! They bailed on the old Gods and started reading the Bible they also edited! Historical continuity and historical rupture must go hand in hand: this is the lesson Foucault teaches us.

Of course it was all way more complicated than this (and I promise this is going somewhere, so stick with me), but this account basically gets us to the 1500s or so when the Protestant Reformation takes place. If you grew up in a Protestant church, you know the story: the evil Catholics got corrupt and started charging people money to go to heaven, but then a nice man came along who felt the Truth of the Holy Spirit and returned the gospel to its true roots. Of course this is nonsense. Luther was writing at a time in which the earliest rumblings of what would turn into the capitalist market was beginning to unfold in Europe as the bureaucrats who actually ran all the land that Feudal lords held were starting to realize they were getting screwed and wanted to capture control of their own land to build their own little empires. What better way to have an ideological structure defending your individual right as a capitalist than a claim that those guys in Rome with funny hats aren’t in charge, but rather Everyone (me) can have a Personal Relationship with God (the market)? In other words, your own LORD? Of course, don’t forget about the printing press and its central role in spreading this idea, which Benedict Anderson has claimed lays the groundwork for Modernity and the rise of the concept of the Nation itself through what he calls “print capitalism.”

It is at this point that the Marxists will tell you that emerging industrial economies in Europe, in concert with colonial expansion and theft of natural resources across the world (as well as the violent re-imposition of slave labor on new populations who are declared to be “outside” history) produced a situation in which the old feudal monarchies and the legal institutions they implemented could no longer withstand the power from below that Capitalism was starting to inject into European societies. England had what was called the “Glorious Revolution” in the seventeenth century which didn’t really change much, but the French followed up with their own a century later and literally cut off the head of the king. This eventually spreads like wildfire across the Imperial core. Where today we typically imagine these revolutions as a moment of human emancipation and the rise of individual freedom from oppression—and they were insofar as people were legitimately experimenting with new forms of government, it was dialectical after all—what really happened is that the King’s managers basically took power and reorganized society under their control. Marxists call these guys the bourgeoisie.

Now, you may be asking yourself how Asia and Africa fit into all this, which is a legitimate question and one that the best historians have been addressing since the 1960s when World Systems Theory began to combine the insights of traditional Marxism with a more global view, armed with a critique of imperialism and colonialism. Marx gave this an earlier shot with what he was able to gather in the British Library during the late nineteenth century, calling it the “Asiatic Mode of Production,” but this mostly pisses everyone off these days for its problematic sounding name even though he didn’t mean it that way, but it does expose a problem with OKAY OKAY, I’ll stop here and talk more about this and what happens next in another post because this is getting long.

Graeber and Wengrow hate this story. I think some of their disagreement comes from the fact they are (and were, RIP Graeber) academics who came of age during the last days of the Cold War where “Soviet Totalitarianism” was still a Big Bad, and that true emancipatory politics need to be horizontalist and reject power in order to replace it with like, consensus or whatever. Thankfully, the past ten years or so have ushered in a turn back to Marx, as millennials indebted by 2008 (along with the older folks who had figured all this out earlier) pointed out that horizontalism is ineffective and doomed Occupy, and that if we want to stop the Right from taking over society we actually do need power and not just good vibes. This is where we return to complaints about the Anti-Imperialist Umbrella. But I digress. Graeber and Wengrow’s argument is that all this is some kind of Bad Imaginary, one which can be overcome with a New Imaginary or some naive bullshit like this. That’s not really fair, but my blog my rules.

But G&W do stumble across an important insight: the rise of organized society and “politics” may not have actually started with the neolithic revolution. Recent archaeological evidence shows that many societies long after their neolithic revolutions organized themselves into radically different experiments with political organization, some of which lasted well into the twentieth century even in societies that had mastered agricultural production. Some societies practiced agriculture for a while and then abandoned it. Others, such as the indigenous groups in the Pacific Northwest, engaged in slave economies that would make Europe blush, while matriarchies emerged elsewhere. Many African societies still structure the distribution of their surplus through gift economies in areas of the world that have evidence of earlier sedentary architecture (you can see how this idea can get dangerous really quick). I think this is an important insight. But also I don’t think it really matters all that much for us in a post-industrial society facing ecological catastrophe and armed with nuclear weapons. This stuff is here to stay and you can’t undo it without setting us back thousands of years and offing a lot of people, and I don’t want to give up air conditioning and the electric guitar.

All of which is to say that Dawn is a fascinating book that contains some pretty serious historical errors. But reading it after Bernie’s collapse and the rise of a world-historically transformative pandemic helped open a door in my brain to thinking about the Meaning of History in a new way. Not just recent history, which had now migrated into the headlines with claims that Trump was going to dismantle the “postwar global order,” or that Fukuyama’s End of History was itself ending. Rather, it got me thinking about new questions such as what kinds of structures and phenomena might still be with us that long predate capitalism? Most serious thinkers are allergic to claims that certain appearances in contemporary society have been with us unchanged since The Dawn of Time. Undergrads love writing papers that open this way. Since the Dawn of Time People have been fighting each other, and stuff like that. Steven Pinker made a career spouting this nonsense and he gets paid millions of dollars and teaches at Harvard. Critiquing this tendency is a necessary move that allows us to resist the intellectual and ideological strictures that emerged alongside the rise of history as a discipline in the German Academy during the nineteenth century and which gave rise to positivism as well as racist arguments that defended colonialism as a “necessary” stage in the development of “primitive” societies.

But like Walter Benjamin reminding us that “the current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth (or twenty-first) century is not philosophical,” this doctrinaire anti-foundationalism has its risks, too. For instance: it is true that Greek society had a radically different conception of the individual. Some have argued that its possible that people living in these societies didn’t have internal dialogues or consciousness the way we do (I’m skeptical but think the weak version of this argument might have some legs). But those societies did have people living in them. And they fought wars, which we still have, and they had sex, which it turns out has meant radically different things in different societies but ultimately has always orbited around the socially necessary phenomena of biological reproduction, pleasure, and power.

As a Marxist, you’re not really supposed to credit Foucault with much, but he was and remains very important to my intellectual development. Foucault is famous for complicating this kind of historical thinking. In The History of Sexuality he makes the convincing and provocative argument that Early Modern European societies invented homosexuality. This might be triggering your alarm bells, but what he means is that people have always had sex with members of what we now call the same sex. It happens in the animal kingdom. But there was no concept of “the homosexual” as an identity that defined an individual, say, in Ancient Greek society. It was just a thing that some people did. Having sex with young boys was a political act in Ancient Greek society and we now lock you up if you try to do that (which has nothing to do with gay people today despite what the Evangelicals want to tell you, because we aren’t Ancient Greeks). But as feudal and eventually modern societies were beginning to spread across Europe to better facilitate the growth of markets and populations for labor, Christianity needed to develop some technology for reproducing its labor force. Enter: “Your” Sexual Identity. You can have a “normal” one, or you can get in trouble for breaking that norm. This is where a lot of irony comes in because Foucault, as a gay man, was basically screaming under flashing red lights WARNING WARNING WARNING! DO NOT LET SOCIETY PRODUCE KNOWLEDGE ABOUT YOU, RADICALLY FREE AND COMPLICATED YOU, IN ORDER TO FIT YOU INTO A CATEGORY THEY CAN THUS CONTROL! But of course nobody read that part and this is where I probably shouldn’t say anything further except to express my unwavering solidarity with Trans and other queer folks about what is coming down the pipeline in the second Trump administration.

Ok. So what I wanted you to get out of this is the following: we should resist the temptation to think about history either as an unchanging Nature in which existing norms have just “always been this way” and instead as products of history, not even as stable objects like “sexuality” that has changed meaning from time to time, but sometimes, as brand new ideas that never existed before. But similarly, we should be wary of arguments that always try and tell you that “it” was like “this” “before capitalism,” that we lived in some kind of blissful state until capitalism emerged, and so on. Academics make this mistake more often than they should, even if they know it to be wrong. It produces a kind of historical amnesia, one that Fredric Jameson has been warning us since the 1980s has taken over as our dominant conceptual mode of thinking that even professed leftists fall into all the time.

If you’ve stuck with me this whole time, kudos, and I promise everything isn’t going to be this long and complicated. The reason I wrote all of that was to explain what led to this Marxist Atheist’s newfound interest in “religion” and why I think we need to understand it not through studying the truth claims of this or that religion, or to insist on the “need” for tradition or some bullshit like that. Rather, I want to ask what would it look like to think of what we call “religion” as a social technology with discrete historical formations, one that has been used by power to enforce control and establish hegemony just as much as it has always been a constitutive component of the human animal’s embeddedness in “the prison house of language.” This is a basic insight I am pulling from Lacanian psychoanalysis, and one that psychoanalysis has long attempted to answer, albeit often without the Marxist account of materialist history. Psychoanalysis does have a long entanglement with Marxism, which is why I’m comfortable doing this. However it often focuses on the way capitalist societies, structured as they are by the centrality of the commodity and the production of “value,” impose themselves upon the individual. That stuff is of course interesting to me, but my question runs adjacent to this insight: I want to explore the question of myth that possessed both Freud and Jung near the end of their lives, but through the insights of Lacan, Foucault, and Marxian economics. Where Freud thought the psyche was a construct resulting from drives that filter through the unconscious (psychoanalysts, don’t get mad at me if I fuck this up) and which are structured mostly by sex, Lacan redirected his analysis into the realm of language: that the unconscious is itself structured like a language, that our brains, our identities, our relationship with others, our metaphysics, literally the entire package, is a result of the fact that we can’t actually access the “real” world and that all there really is between us and it is a layer of language that helps us make sense of the entire thing. And we invented it!

On the one hand, this is just unreconstructed Kantianism. But on the other, it’s a theory about human society and the psyche that I think helps make sense of the diverging intellectual trajectories of Freud and Jung, the latter of whom was Freud’s heir apparent until a tumultuous breakup the reasons of which I don’t want to get into here beyond noting that Freud’s project went in the direction of biology and sex while Jung got interested in mythology, and symbolism, and ritual. Of course near the end of his life Freud freud found a lot to say about precisely that, but the split had cleaved too deeply. Jung became anathema to the left (and admittedly had some weird things to say about European Mythology in the 1930s) because he seemed to be a conservative, while Freud provided key tools for the Marxian left. Today Jordan Peterson seems to be the intellectual heir of Jung’s tradition, which is an insane thing to say because, you know, Jordan Peterson, but it gets at where some of this stuff ended up.

But still, I found simply calling all this bourgeois mystification to be deeply unsatisfying, especially when I entered my own crisis of Meaning as a direct result of the trajectory of the left. I read Graeber and Wengrow at this moment because I wanted to gain a broader view of history than the one I had been stuck in during my phase of Marxist exploration, which introduced me to epochally transformative accounts of the rise of capitalism and its various stages, but had little to say about what to do next beyond shrugging shoulders and saying welp, it’s gonna get bad. Pace James C. Scott, I wanted to see history and Meaning like a historical materialist, I wanted to see culture like a total historian, an alien removed from our development here on Earth studying all the moving parts down below. I know that you can’t actually remove yourself from that history, that positivism is the lie that tells you you can. But one important fact that I became more aware of in this whole process quickly became clear to me: in every social formation we have ever had, certain problems keep emerging that are not unique to the contradictions of the capitalist mode of production, problems which will remain ostensibly long after capitalism has vanished from history. Now, this is precisely Marx’s argument—the basic insight of historical materialism—but the increasingly destructive crises of a now global capitalism force many of our best thinkers into a kind of myopia that causes them to ignore this mode of historical thinking for a certain kind of presentism in the face of the emergency at hand.

Here are the questions I want to explore in this project: what, exactly, are the practices, concepts, functions, and utilities that comprise the conceptual apparatus we have come to call “Religion?” How do these activities mutate over time as we pass from one mode of production to another? What remains in our societies of the practices that encompassed what we call “primitive” religions (ancestor worship/fertility cults/Sun and Moon worship, etc), practices that may or may not have been sublimated into new religions formations or abandoned them altogether (the classic formulation of this is how “Christmas” came to replace “pagan” solstice rituals practiced by earlier agricultural societies…but what if ancestor worship wasn’t merely a conceptual error but rather a temporal structure that helped lead to capitalism’s capture of the past through debt instruments and its claim on the future?) How should we as Marxists conceive of religion? Not as the famous “opiate of the masses,” nor as a mere ideological structure imposed on us by the interests of the ruling class, but as a kind of force that has been transmitted through all time in discrete mutations (I don’t mean this in the supernatural way, but rather “force” in the sense that pushing a rock off a cliff transfers energy from one thing to another and has a resulting forceful effect)? And finally, how should the left reconstruct whatever transhistorical necessity “religion” served for earlier societies in our own postmodernity, after the “Death of God” and disenchantment of the world? In short: what if the left’s project required a synthesis of Freud and Marx to make sense of the coming of industrial modernity and its impact on the psyche, but now that modernization has completed, and we are facing the complete capture of the social and symbolic by algorithmic commodification in every aspect of our experience, we need a Jungian-Marxism to make sense of postmodernity?

Overtures to Jung typically make leftists nervous, and for good reason. There has been a long history of the left turning inward after historical defeats; the boomers all fleeing to New Spiritual Movements and Evangelical Christianity in the 1970s attests to this, as does the uptick of astrology on social media after the election of Donald Trump in 2016. “Actually, what we need right now is a Return To Meaning and hey, it sure is convenient we can find that in this religion that feels older than capitalism!” is why the teens are now converting to Catholicism instead of smoking weed and trying to sneak handjobs in the back seat. But this intellectual interest in religion need not be any kind of displacement, a symptom of a political loss the cause of which can only be overcome by going back in time and doing the Revolution the right way—the same nostalgic impulse that gives rise to the Trad Caths! The left has typically responded to the Inward Turn by bemoaning the loss of collective agency, doubling down on an obsessive moralism that wants to find a cause to blame for the dialectic not resolving. But if we keep doing this shit after we lose, maybe its because we never resolve this contradiction and return to it each time like a dog to his own vomit.

This is some of what I’ve been thinking about over the past few years. I should wrap up this very long post up by telling you that I will be exploring this in the future on this blog, and I will try and tag articles appropriately so you can tap out when you aren’t interested. I want to articulate that what interests me about this is how the left can learn from this project, that I am not interested in leaving the struggle for a kind of Christopher Lasch, Red Scare, Trot-turned-neocon phase that has happened again and again (which you can find all over Twitter/X these days). I am interested in stopping that from happening, in countering the Jordan Petersons of the world with better accounts that speak to the very emptiness that young Peterson fans—alienated young men—are feeling as they try and make sense of late capitalism, who are currently only finding answers in malevolent misogynistic freaks like Andrew Tate or pseudo-intellectuals trying to hawk nutrition supplements at them. But this is not just a Guy thing—I think this is a crisis of meaning we all face at this moment in history.

Whatever that looks like is up to how this project unfolds, and I promise you I’m not going to turn this into some kind of outreach program. I am ultimately interested in these questions as an leftist first and academic second. But I think this is necessary work for our historical moment, and it’s also necessary work for me at this point in my life as I go through a pretty tumultuous life transition I hope to be able to speak about with a healthier understanding of how I made it to the other side.

Fuck yeah. Awesome.

In a similar way that Marx never really finished his intellectual project(part of his genius is that he was well aware of some of the deficiencies of his own framework and always self-correcting and non-dogmatic), it seems the concept of the "dialectic" is itself an unfinished idea and leftists have been running their engines on the equivalent of a suped up steam engine for the last 150 years. The fact that we are seeing "unresolved" dialectics probably indicates something is wrong in our conceptions in this whole "history" thing(maybe so much so that Marx maybe shouldn't even be our primarily weapon anymore but that's a whole other impossible to think about thing).

Dialectical thinking seems too tied to the "Di-" prefix, and wondering why it is always finding itself in double-binds and sharp turns into desperate moralism.

R. H. Tawney's Religion And The Rise Of Capitalism is a historical account of how these religious forces were present in the construction of capitalism. imo, for this specific contemplation of religion Tawney is even more important to consider than Graeber & Wengrow's Dawn.