History's Camera (on Fredric Jameson, 1934-2024)

An obit for Fredric Jameson I wrote last year.

Late last year I pitched and wrote an obituary for Fredric Jameson following his death in September at the ripe age of 90. It was intended to run for an audience more familiar with cinema than theory and philosophy, and so the piece was framed with that address in mind. The editorial process went well and we were close to publication but (Adam Curtis voice) then a funny thing happened: the world started falling apart at an even faster rate than it had been over the past few years. The news cycle began to take on a life of its own, and film festival season hit (Godard and Truffaut at Cannes ‘68 this wasn’t). Obits are time-sensitive, and because we had spent more time on development and conceptual angle than hitting the news cycle it’s been in development hell in various stages all year. I asked to have the piece released back to me and now I’m releasing it into the wild, for you.

I’ve been way too AWOL on here for way too long, so please accept this as some Hot Content for your eyeballs as recompense.

History’s Camera (on Fredric Jameson, 1934-2024)

Fredric Jameson died last fall, still working, at the age of 90. Sometimes when influential figures in the creative world leave us, their obituaries begin with phrases like “best known for his,” or “her most celebrated achievement was,” but Jameson was one of those figures who leaves a body of work and influence so vast that it can really only be umbrellaed under an eponym. To call something Jamesonian makes reference not merely to the key ideas he generated in his role as a comparative literature professor at Duke University or texts from his voluminous list of publications that spans best-selling books and capsule reviews of films, novels, and the political news of the day. The adjective Jamesonian has come to signify instead a mode of thinking, a critical approach toward aesthetics and politics, and importantly, a commitment to historical thinking at a time when capitalism has annihilated all temporal horizons beyond the perpetual present of the marketplace. His famous exhortation to “always historicize” didn’t merely offer us a new strategy to read novels or watch films against the grain; it connected us to an ongoing and collective struggle to “wrest a realm of Freedom from a realm of Necessity” that began long before his time and which will continue past our own.[1]

Jameson located this struggle within the Marxist intellectual tradition. But his politics were not concerned with things like party doctrine or proselytizing from the holy texts. Jameson was interested in analyzing the “utopian dimension” in films like Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), and in using HBO’s television series The Wire (David Simon, 2002-2008) as a “cognitive map” for understanding the complex political, economic, and cultural structures of an American city in the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries. Such “political” readings of popular media texts may seem ubiquitous in the social media era, but Jameson began his work at a time when it was still legally dubious to identify as a Marxist in the United States, amidst scholars who refused to take seriously any art that dare be found outside of the museum’s curated white cube. During this time he saw—and named—the transition out of the high modernist artistic and intellectual culture of the early twentieth century that gave way to a cultural logic of “postmodernism” we still inhabit.

His interest in mass culture—and cinema in particular—illustrated this historical transition that bookended the ten decades through which he lived. As a result, his scholarship ranges from science fiction novels to Gustav Mahler, German philosophy to Hollywood cinema, architecture, painting, Soviet film theory, from the role of the “national allegory” in so-called “Third World Literature” to psychoanalysis—sometimes all in the same book. The point of unspooling such a tightly-woven thread is not meant to overwhelm his reader but to help them see the ways in which capitalism, in its multinational form that took shape during the late twentieth century, presents us with an unsolved challenge to represent it without simultaneously giving us the adequate tools to do so. Especially not to critique it! Cinema’s centrality to his work was thus not merely due to its nature as the dominant mass media form of the first half of the twentieth century in which he grew up; it was because Jameson wanted to teach us to see capitalism through a camera that had yet to be invented.

The best name we have for that camera might be history itself. His own can help situate the reasons for his vast literacy across the multiple aesthetic forms that rose to prominence during his lifetime, and the position from which he was able to synthesize such a gaze into a focused project. Jameson—whose penultimate book was recently published from a seminar he taught via Zoom during Covid-19—entered college in the 1950s, just as the modernist art movement was entering its final phase. He graduated with a PhD in French Literature from Yale in 1961, writing a dissertation on Jean-Paul Sartre and existentialism, a rare move for an American student at a time when European intellectual culture and its dalliances with the left was looked upon with skepticism by a culture that had just gotten through McCarthyism and the Hollywood Blacklist.

Jameson was a voracious reader since his youth. By early adulthood he became inspired by the “world literature” approach of poets such as Ezra Pound (who was alive at the time, remember), who wrote with a type of fragmented, totalizing method of narration and structure. Pound’s The Cantos (1915-62), for instance, assaults its reader with everything from Chinese logographs to references to medieval Italy and the founding of the United States, and then forces the reader to piece it all together. What this must have been like for a young reader! And not unlike a prototype for a Jamesonian argument about multinational capitalism save for a missing explicit commitment to emancipatory politics.

That’s how Jameson read. And read he did. His interest in aesthetic movements calling themselves things like “world literature” later provided him the opportunity to read William Faulkner through the French theorists who had started to turn the European academy on its head. This act of historical and linguistic translation was happening at a time when Faulkner’s work had mostly fallen out of print in the United States in favor of a new generation, but picked up by an exciting new philosophical movement that had been injecting new life into continental philosophy after the end of the war. If you were going to read the greats in the 1950s, this was one way to do it; analytically, American art seen through a European’s eyes.

At some point in his studies he was turned on to the work of the exiled German writer Thomas Mann. Because he learned how to think the way he did, Jameson eventually discovered that at one point during the writing of 1947’s Doctor Faustus, Mann had gotten in contact with a then-little known philosopher named Theodor Adorno for help researching music. Doctor Faustus is a novel that allegorizes Germany’s Nazi catastrophe through the life of its protagonist, a talented German composer who re-enacts Faust’s bargain only to find his life unravel into chaos and madness. Had this novel only influenced Jameson’s lifelong interest in allegory, it would still have been an upset, but you have to think about his later commitment to finding a way out of conspiratorial paranoia, something that only an effective and true cognitive map could provide. Jameson’s engagement with history didn’t end at thinking about it either. To this day many American college students first encounter Adorno through a book that contains Jameson’s own work.

When listening to Jameson talk about these early interests in a 2014 Madrid lecture, one cannot help but think of what it feels like to go down a hyperlink rabbit hole on the internet. Such maze-like conceptual exploration feels like a product of being online in our hypermediated digital age. And yet, Jameson was practicing this interdisciplinary mode of curation more than a decade before the rise of home video, or even the photocopier, made such pastiche widespread. This style of intellectual bricolage is precisely what allowed Jameson to see what was happening to global culture before it hit the rest of us, so to speak: by the 1960s, capitalism had not only set foot in every corner of the globe, it had begun to gobble up history itself to offer on a plate to the discerning customer through cultural forms like cinema, mass market print, television, even architecture, which in Jameson’s youth was undergoing its own postwar tranformation as the Western world began preparing for domestic peace. At that point, still in a mostly analog media culture dominated by print, celluloid, and broadcast technology, such breadth was something that only a French-reading American graduate student with an interest in modernist poetry and detective novels could understand.

But what would come next would take it out of the ivory tower and into Warhol’s prints of Campbell’s soup cans and the screens of the multiplex, stills of which began to be reproduced in this pages of his books alongside Jameson’s freely associative art history. Jameson’s interest in European philosophy and modernist literature was producing a philosophical consciousness that was also spending a lot of time at the movies. Faulkner on Wednesday, George Stevens on Friday; Jameson was capturing the last of modernism as it was departing the historical stage, leaving little crumbs behind in melodrama and the Saturday movie. Jameson saw in Hollywood film the same recognition of aesthetics and politics that may emerge from a more acculturated reading of the European avant-garde. And he was read by others who wanted to think about film—America’s true pictorial art form—the same way. His influence over film culture in America is not merely the result of three generations of film students having been assigned his essays in college; even Ti West’s MaXXXine (2024) seems indebted to an essay he wrote connecting the Westin Bonaventure Hotel with the nostalgic pastiche of 1970s Hollywood cinema.[2]

It wasn’t just Hollywood, of course. During the 1960s, Jameson studied in Germany and brought with him his interest in the French structuralism he had picked up in graduate school. Soon he found himself deeply invested in the dialectical tradition of German philosophy that ran through Hegel and Marx, and which took shape on the streets of Paris in May of 1968, filmed through the cameras of Chris Marker and Jean-Luc Godard. As the oft-repeated story goes, both directors emerged first as critics in of the postwar French cinephile culture of Henri Langlois’ Cinémathèque Française and the literary flourishings of André Bazin’s Cahiers du Cinéma, which by the late 1960s had taken an editorial turn towards a hardline Maoism that emerged in response to the global 1968 revolution.

But if the cultural trajectory of French cinephilia traversed this same intellectual path that Jameson had taken, from the existentialist humanism of youth to a politically salient historical materialism in the face of an emergent historical situation, the story was not the same for American cinema critics. While the American 1968 was in equal parts transformative, decades of anticommunism had extinguished a fully conscious Marxist cultural project from both the US Academy and broader cinema world. Jameson’s return to the US—what he calls the “homeland of mass culture”—thus marked yet another stage in his intellectual development, honed by the rigor and politics of a Europe where Communist parties shared in ruling coalitions with Western governments, and with an arts culture that had few counterparts in the US, save for the last remnants of the radical avant-gardes in New York and other urban metropoles.

Like his encounter with Faulkner, Jameson watched a lot of Hollywood movies both in Europe and back home in the States. His professing landed him various teaching appointments from Harvard, to UCSD, Yale, and UCSC. If the postwar lifting of the Nazi embargo on Hollywood films opened the eyes of young French critics to the world of the auteur theory and cinematic style, Jameson saw in Europe’s uneasy acceptance of Hollywood film distribution a moment of cultural translation mediated by a global market, conscious of the need to expand in search of new markets but in local contexts. His intellectual forbearers watched movies, even while they scoffed at the dangerous nature of the Culture Industry (later in that 2014 talk he notes that Adorno would attend Hollywood films “three or four times a week, bad movies of the kind he would condemn”). Here is that camera of Jameson’s, “seeing” the history of twentieth century philosophy through the eyes of historical experience that only a French-speaking, Hollywood cinema-attending American cultural critic into Hegel could possess. He claimed to have seen every film released in his local theater growing up between 1943-1950, and then in his time in Europe, he saw these same films exported to adoring French audiences through a glass darkly; here was the first taste of the kind of globalizing mass culture that would soon occupy a central role in his academic work. When the French did this they came up with the Auteur Theory and created a mythos for cinephilia we still re-enact on Letterboxd. Why can’t we do the same for Jameson’s version?

Following the end of the 1968 global revolution, Jameson spent the 1970s crafting his synthesis of French structuralism and German dialectical thinking into an aesthetic project of cultural critique he would announce in 1981’s The Political Unconscious. The book—which begins with a magisterial, 100-page elaboration of a critical method of reading cultural texts “symptomatically” so as to learn from what they don’t say, which can point us to our culture’s broader “political unconscious”—still remains fixated primarily on literature. However by the mid-1970s, Jameson had begun to take note of the broader cultural landscape of American mass culture, which by that point had exploded out from the diverse reading lists he encountered as a French graduate student and onto cinema and television screens, travel literature and advertisements, pop art and the international films that now came to him, teaching in Durham, North Carolina at Duke University, where he would remain until his death last fall.

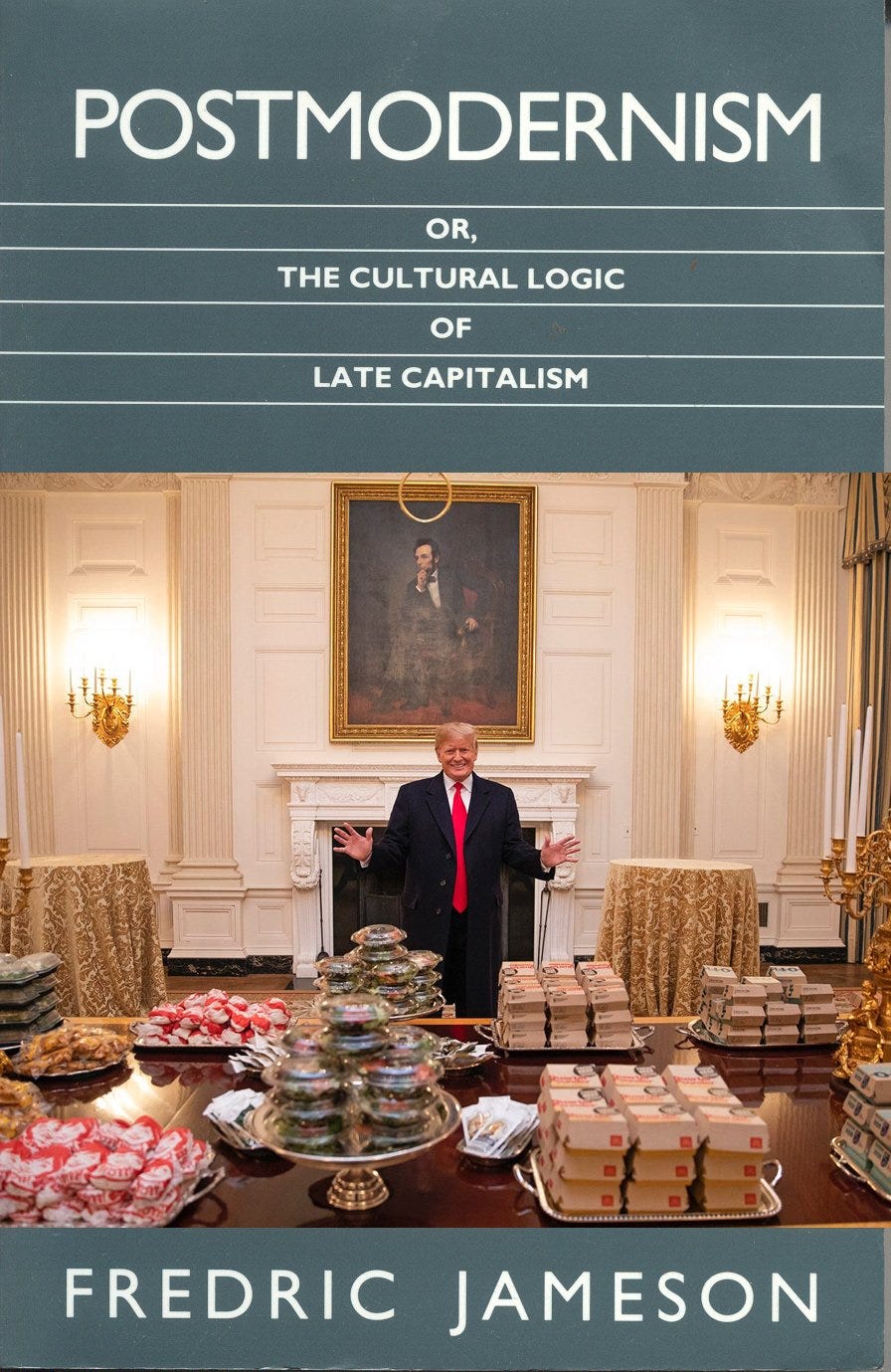

His research from this era culminated in his 1991 masterwork Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Like that early Jameson, “clicking” through the hyperlinks of modernist literature before the internet gave them concrete form, this Jameson describes a world where those links can actually be clicked on, opening windows into new forms like video art, museum gift shops, nuclear power. By this point, Jameson was even more of an ideological rarity in the American academy. If his Marxism was politically questionable during a decade where politically-motivated bombings and plane hijackings dominated the news, by the late 1980s Marxism seemed like an exhausted project. The Soviet Union was collapsing, and with it, a sense of any alternative to a globalizing capitalism that now literally was in every corner of the globe.

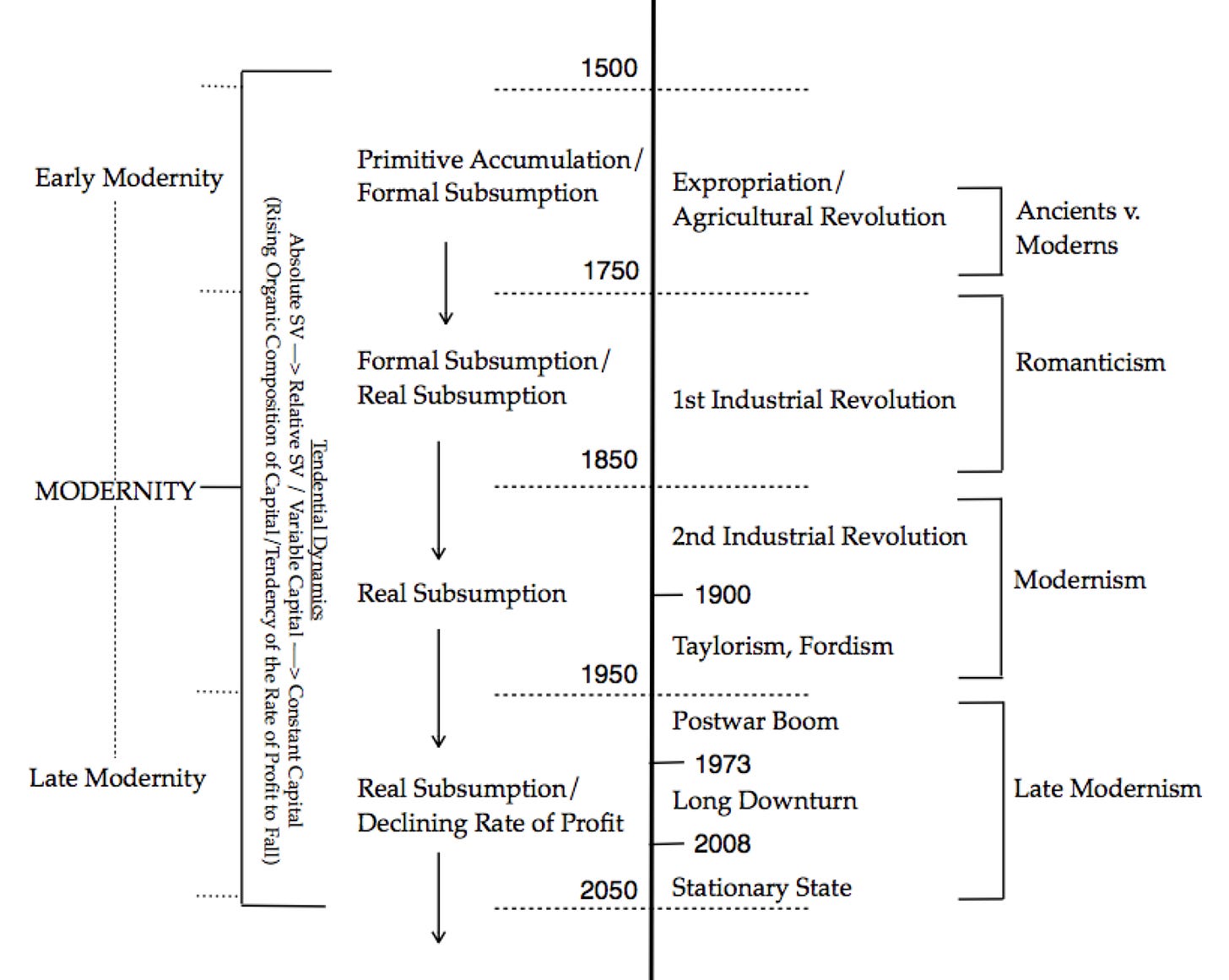

Borrowing a term from Marxist economist Ernest Mandel (who himself borrowed from political economists writing in the 1920s), Jameson gave name to what he saw as “late” capitalism’s now-dominant “cultural logic,” which he called “postmodernism.” Postmodernism to Jameson is not a style but rather a period, one in which “aesthetic production…has become integrated into commodity production generally: the frantic economic urgency of producing fresh waves of ever more novel-seeming goods…at ever greater rates of turnover, now assigns an increasingly essential structural function and position to aesthetic innovation and experimentation.”[3] Where art in earlier societies—even earlier phases of capitalism—retained a partially autonomous sphere from the market, it has now been completely subsumed by the market; even aesthetic critiques of capitalism cannot escape its totalizing logic and commodification. Postmodernism remains Jameson’s best-selling book to this date.

In Postmodernism, and its earlier drafts, Jameson introduced the idea of the Nostalgia Film (or mode, as he would come to call it). This might sound like old hat to us now, but when he posed the idea in the early 1980s he wasn’t thinking about literal reboots of Star Wars that brought the old cast back together for One Last Ride (to a shopping cart on Disney.com). We like think of the culture of our age as one enslaved to nostalgia, but Jameson saw this was already taking place in the 1970s; Lucas’s 1977 film referenced Kurosawa and Buck Rogers sequels, reaching back to the media he consumed in his youth. just as the 2010s Star Wars sequels were references to their own earlier iterations, the intellectual property of which is of course all conveniently owned by the Walt Disney Corporation. These aren’t just personal choices, they are logics that have been forced upon aesthetic production now that forms such as cinema and television have their own history to reference.

To Jameson, this was all a symptom of our inability to place ourselves in history in an age dominated by media representations of it, to effectively know when we are amidst an endless stream of photographs of the past or films depicting how it may have appeared. Jameson didn’t think of the nostalgia mode exclusively in terms of movies referencing other movies. He included in this category films such as Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat (1981) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970), films which were either set diegetically in the actual past or in some strange in-betweenness: a past which can only be grasped through aesthetic representations of what we think it looked or felt like back “then,” since we can only access it through representation. What if, for instance, Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973) wasn’t actually “about” its 1950s setting of drive-in diners and cool hot rods, but rather his generation’s incapacity to see any kind of path forward in their own lives after the tumult of the global revolution of 1968, the economic crises of the early 1970s, the terror of being called up to serve in Vietnam? Today, the nostalgia mode is similarly not “about” the past—Stranger Things is “about” John Carpenter movies and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II (2024) is “about” his own Gladiator (2000), which itself was “about” 1960s sword-and-sandals epics—but what they are actually about is our inability to feel like we are headed somewhere we understand. “History is what hurts,” Jameson once famously quipped, and one way I’ve understood that is that it always seems to rear its head when we least expect it, due in large part to the fact that we haven’t quite figured out how to grasp hold of it and steer it in the direction we know it needs to go, leaving us with nothing but the gap and an unfulfilled desire that can only be met with political commitment.[4]

In the years following the publication of his works on postmodernism, many cultural theorists took his ideas merely as I expressed them above. Blade Runner (1982), for instance, is a pastiche (Jameson’s term) of 1940s noir and the science fiction genre Jameson loved so much. And isn’t that cool? Postmodernism’s blurring of the line between high art and “lower” forms encouraged a situation in which potential artists might not be gatekept by elitist snobs. This is what some critics took from the book, including figures like Linda Hutcheon, who began reading pop cultural texts not symptomatically as Jameson suggested, but as containers of emancipatory potential for audiences newly visible to transformed modes of market research. But, again, Jameson warned us that postmodernism was not merely a style, it was a logic—in fact, it was the logic of capitalism itself transmogrifying out of its now-completed stage of industrial development in Western factories and local agricultural production now to screens, social media, even our consumption of art as a commodity itself. When Jameson speaks of postmodernism, he was really speaking of postmodernity—a clarifying, periodizing term that reminds us that capitalism is not in its final stage but that nineteenth and early twentieth century modernity, with its great artistic masters and heroic struggle between workers and capital, was indeed over, and we might not like what comes after.

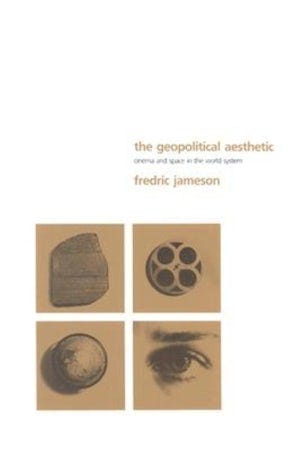

Because Postmodernism came to offer a periodizing method and term for the work of art in the age of digital reproducibility, Jameson gathered his writing on film from the period into two texts that stand as his most explicit forays into film theory. The first came with 1990s’ Signatures of the Visible, which reads Jaws, Dog Day Afternoon (Sidney Lumet, 1975), and The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) as allegories of an America losing its historicity as it groans into the very postmodernity the New Hollywood that put them on screen. The book closes with an essay titled “The Existence of Italy,” in which Jameson offers American film theory’s first real great contribution to the debates on cinematic realism inaugurated by Bazin and the postwar Italian filmmakers by challenging the idea of the indexical trace in photochemical film, expressed in the long take, as something which is always already filtered through a kind of visual translation of cultural space that the viewer imposes on their interpretation of what is represented on screen (it seems fitting an American reading French and quoting German would be the first to see this). But it was with 1992’s The Geopolitical Aesthetic that Jameson contributed to the film theoretical canon his next great idea: that of the conspiracy mode, 1970s Hollywood’s other great formal innovation into film genre that emerged from a specific historical moment and its influences.

The Geopolitical Aesthetic adds to conspiracy thrillers readings of then-recent films from the Taiwanese New Wave, Third Cinema, and Godard, who remained a touchstone throughout his life. Where a more traditional film scholar might feel hesitant to dip their toes into the controversial “transnational cinema” approach for fear of flattening difference or reading the West into postcolonial areas of the world reclaiming their own history, Jameson saw a throughline between these disparate films that was not merely humanist in nature but diagnostic of the nature by which capitalism was entering its era of complete global spread. He got in trouble for this, too, but he remained steadfast in his insistence that his quest to find in art a way of understanding all of our experiences of global capitalism was not only a useful way of thinking but urgently necessary. What good comes from drawing impenetrable lines between Kidlak Tahimik’s Perfumed Nightmare (1977) and All The President’s Men (Alan Pakula, 1976) if it doesn’t allow us to see that both films are responding to the same decolonizing world: a world that could usher in one man’s disillusionment with the West he so admired, and two others’ attempt to take down the President of the United States involved in the carpet bombing of the other side of the globe?

These films’ representation of the “degraded” attempt to map the spatial totality of the global capitalist world that was emerging as the twentieth century was drawing to a close illustrated to Jameson our need for better cognitive maps, but the irony is that we now hold in our hands technology that can instantaneously connect us to any part of the globe at the drop of a hat. And yet, we remain just as lost and confused, conspiracy runs rampant, our lack of utopian thinking, he once quipped, makes it easier to imagine the end of the world than capitalism itself.

But while his world groaned on its axis, spinning towards an uncertain future, he remained committed to his vision of the world expressed most clearly one hundred years earlier, that distance from his present a reminder that the now is always full of the potential to break in another direction, if we can see it. Central to Jameson’s commitment to the Marxist project was his repeated insistence on the need for utopia, for utopian thinking—not that ideas will save the world, but rather that the core of emancipation must always be tied up in the belief that the world could be made different than it is, and that our lack of utopian visions in art is rather a symptom of our general inability to actually act on it.

It would behoove us to remember this in our own time, as global catastrophes fill our social media timelines and conversations about theatrical slop convince us that there’s nothing of value waiting for us down the line. Art feels bad these days? Figure out what it’s not saying so new language can take form for thoughts we have yet to speak. You can’t imagine the world without capitalism? Maybe first we have to learn how to see, using a camera called History, which we have yet to learn how to operate to its full potential.

Correction: An earlier draft described Jameson watching films “back home in Ohio,” which was a breezy paraphrase of Jameson’s own account in the embedded video. I was too loose with this, and was helpfully corrected by one of Jameson’s own students, Ethan Knapp, who teaches in Ohio and knows a thing or two about both topics! Jameson’s American filmgoing began later, when he was living in suburban New Jersey. Thanks Ethan!

[1] The Political Unconscious. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981, p. 9, 19.

[2] “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” New Left Review 146, July/Aug 1984. < https://newleftreview.org/issues/i146/articles/fredric-jameson-postmodernism-or-the-cultural-logic-of-late-capitalism>

[3] Postmodernism, Durham: Duke University Press, 1991, p. 4-5.

[4] Jameson, 1981, p. 102