An Emotional History of The Present? on Adam Curtis' "Can't Get You Out of My Head (2021)"

or, i went to grad school for seven years and all I got was this Foucault T-shirt

An Emotional History of the Present?

Matthew Ellis

Imagine if you will you’ve just gotten word of a new documentary miniseries about to drop to critical acclaim. Based on the early reviews, you understand that the series seeks to interrogate the roots of our contemporary political crisis by unspooling what appears to us as history’s tightly wound thread, stopping only to find moments where an accident here or a deviation there led unknowingly to an outcome few could have planned even if they wanted to.

The film’s language leans into the academic, but something about it slots neatly into the contemporary zeitgeist, even if the characters and events seem to emerge out from another lifetime. In other words, it is screened both in seminars and for popular audiences. Its creator is interviewed in magazines and is the subject of special issues in academic journals. It appeals to both the already-initiated and the curious, addressing its spectator with a spirit of trust not often found in popular documentary cinema that tells you not to eat that, or where your t-shirt came from. There is little moralizing and lecturing; instead, a sober yet spectacular narrative that allows the viewer to feel they are making the predetermined narrative connections on their own, as if they were not each outlined in ink before the tapehead or hosted file hit play.

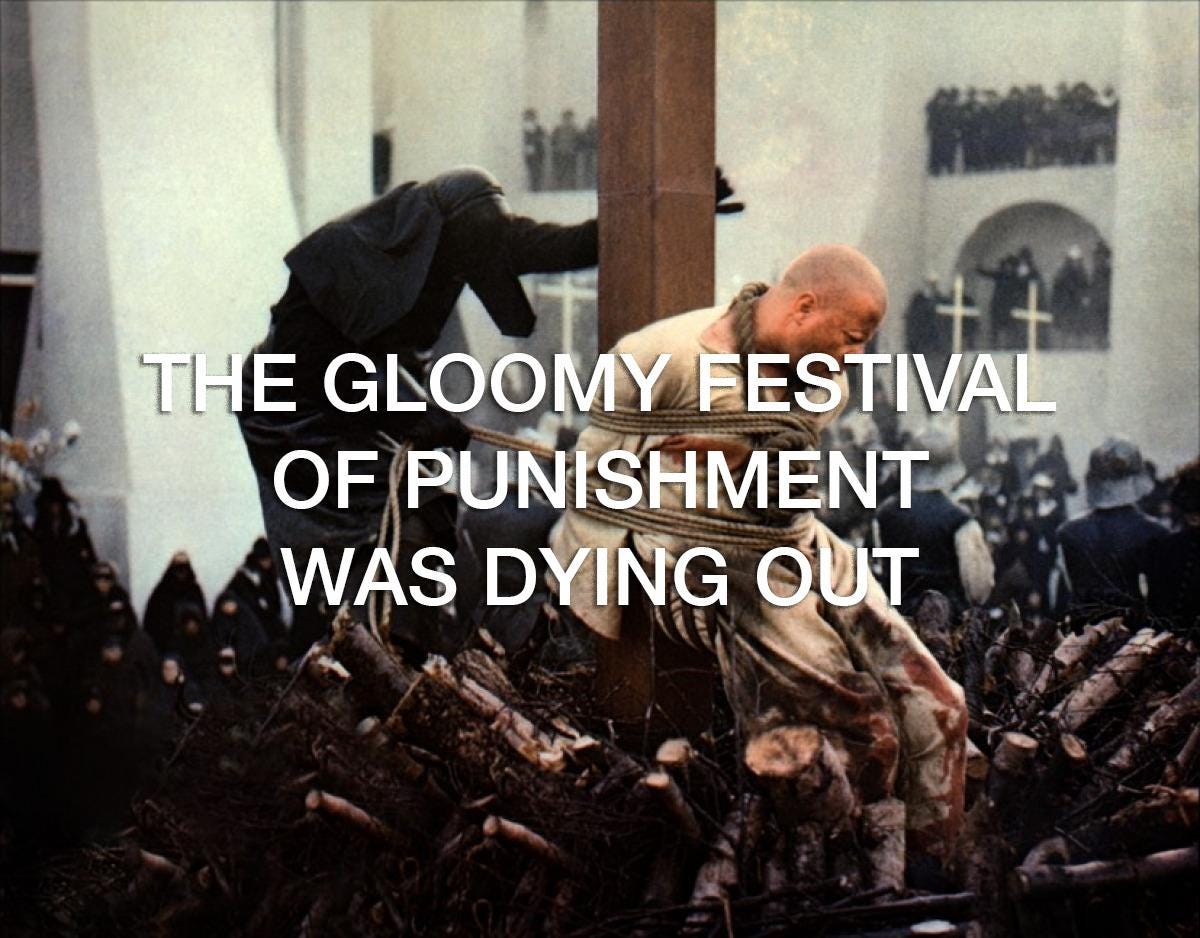

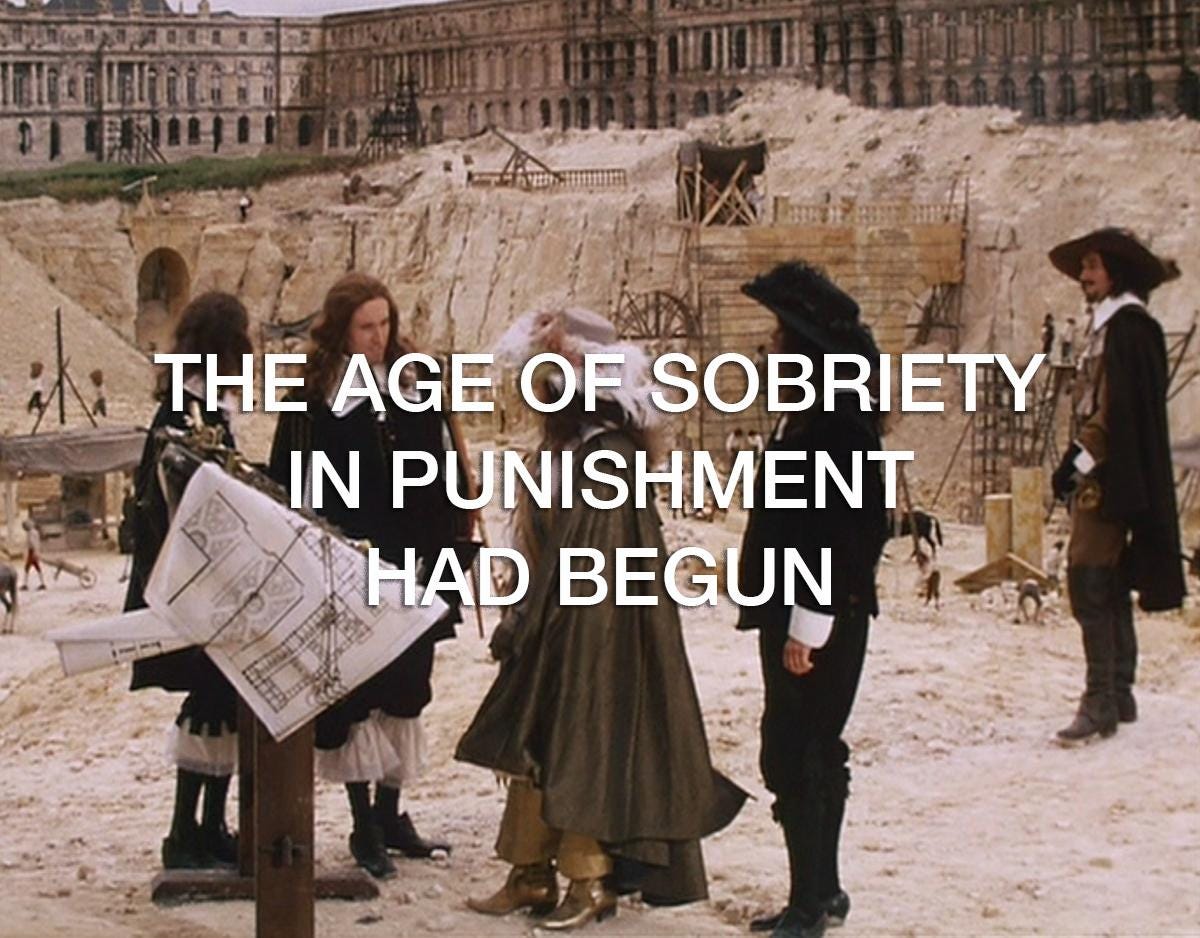

The first scenes might look something like this: a snowy, slurry of a black and white cathode ray image crystallizing until it finally becomes intelligible. You are then able to make out perfectly manicured topiary, lining a gravel road under a noontime sun leading to an ornate seventeenth-century palace. Then, perhaps, a cut to a rat scurrying through blackened water covering the rue Saint-Séverin. Over the opening chords of Handel’s Sarabande on the soundtrack (a cult classic), a cut to grainy 8mm archival footage of King Louis XV, rifling through documents in the court. He is flanked in the foreground by a quietly unassuming character we come to learn is one Maréchal Maurice de Saxe (remember him, he later becomes an important character in Part 4). Then, a scene of bodies lit by candlelight, dancing inside an ornate room walled with paintings depicting national victories from the lore of earlier centuries. A cut to a moldy loaf of bread embraced by dirty fingernails. Finally, a voice on the soundtrack begins,

On 2 March 1757 Damiens the regicide was condemned ‘to make the amende honorable before the main door of the Church of Paris…but then a strange thing happened…

Surveiller Et Punir (Michel Foucault, RTF Télévision 2, 1977)*

*The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971), The Taking of Power by Louis XIV (Roberto Rossellini, 1966)

Let’s be honest: it might be gauche to imagine an Adam Curtis-style film version of the Foucault of Discipline and Punish, the 1970s lectures, or the first volume of The History of Sexuality. It’s tempting, however: if Curtis’ freewheeling associative style has done nothing else for our contemporary moment, it certainly has provided ample opportunity for parody, perhaps something like a formal working-through of the way the crisis of neoliberal capitalism often feels represented best in meme format. Trump, Brexit? Forward-facing TikTok dances while quarantined inside for weeks during a global pandemic? An insurrection on the sitting government of the United States that included an organic food advocate adorned in war paint and a horned headdress? Global commerce at a halt due to a grounded container ship in the Suez canal? One could easily mistake the actual news of these events as images culled from the BBC archives, weakly-threaded together under the calm narration of a British media class accent. And one could perhaps say the same for much of Foucault’s mid-70s genealogical work, in which the spectacle of public execution eventually gives way to the management of docile bodies within state institutions (Discipline and Punish), or grain scarcity leads to the emergence of the twin concepts of population on the one hand and the world market on the other (Security, Territory, Population).

Adam Curtis’ obsessions and method—on power and within the archive, respectively—have long drawn comparisons to the work of Foucault. In an interview with The Wire on the press circuit for 2011’s All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace, Curtis blithely intones that “(p)eople say, oh, you must have read Foucault, and I say, well yeah, I tried it and what he’s saying is so mind-crushingly banal, you could say it in one page.” He goes on to complain of Foucault’s obscurantism—clearly an image-thinker frustrated with the French philosopher’s focus on pages and pages of bureaucratic archival documents rather than the “simple and approachable” or “emotional as well as intellectual” approach that moving images seem able to offer.

But the comparisons between the two exist with good reason, not merely for the way power returns again and again as the conceptual ghost that haunts each of their respective bodies of work. Both seem to locate the genesis of their intellectual curiosities in the dialectic between the individual and the collective (although Foucault would of course bristle at being accused of such a thing). Both express a skepticism of institutions, albeit in quite different ways: for Foucault, the medicalization of psychiatry and the rise of discipline as a governing logic in the West, for Curtis, the rise of Silicon Valley, “money”, for-profit media, and so on. Were you to somehow put both in a room you might imagine an argument arising over simple minutiae or the incommensurable historical experience of their own presents; screen The Century of the Self (2002) alongside The History of Sexuality: Volume One’s attack on the repressive hypothesis and both might become Bolsheviks in the fight against twentieth-century psychoanalysis.

Many of these trite comparisons, however, begin to collapse beyond the level of headline. Foucault was a thinker irrevocably changed by the events of 1968, who, in Daniel Zamora’s account, saw the emergence of a new possibility in the global turn to neoliberalism in the mid-to-late 1970s (“(y)esterday’s fellow travelers became neoliberalism’s facilitators”). Curtis, on the other hand, is a quintessential Gen-X white British cultural critic, disillusioned by what Mark Fisher has termed, following Franco Berardi, the “slow cancellation of the future” with the rise of Thatcherism and the withering away of the postwar welfare state in favor of finance and privatized communicative capital. Foucault’s later work began to investigate the genealogy of “technologies of the self” throughout history from the Greeks to early Christian modernity to the present, while all but disavowing the individual in his early archaeological work. Curtis sees the individual as an ideological fever dream of an exhausted system that has given up on collective visions of the future. Foucault’s reputation as a capital-T French Theorist betrays his intellectual heritage as an inheritor of the postwar turn to philosophy of science and epistemology in the work of Georges Canguilhem. Curtis claims to disavow the left but names as his primary influences Max Weber and John Dos Passos. Foucault, too, was famously resistant towards any overtures to Marxian influences, whether it be his personal disdain for Louis Althusser or the specificity of the situation befalling the French Communist Party during the late 1960s. Curtis is just as critical of the collapsing communist project in Hypernormalisation (2016) as he is of the capitalist west. Both have disciples and followers throughout seemingly disparate left tendencies, from Curtis’ resonance with the Jacobin left in the United States to Reddit “doomers,” or Foucault’s much maligned influence on post-Marxist trends in the post-1980s academy.

But beyond their resonant interests—in power, in mining the archive, in epistemic rupture and discontinuity—might it be possible to argue that Curtis effectively takes from Foucault not a paranoid obsession with power in all its forms, but rather, a sort of fidelity to the genealogical project Foucault began to adopt in the 1970s?

Split screen from Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (Adam Curtis, 2021)

Curtis’ films are certainly genealogical, if only in their narrative form. His characters often appear as ancillary players embedded in deeper histories that unfold over multi-hour running times, multi-part episodes or even, if you will, across multiple films. There are no singular protagonists to a Curtis film, merely a list of begats like a modern scripture outlining the history of a people from whom we have all descended into our own present.

For instance, Herman Kahn and John von Neumann appear in a single episode of 1993’s The Trap, a film about the emergence of technocracy from the Soviet bureaucracy to systems analysis during the Cold War, and of course, the spread of DDT and its impact on the environment (obviously). Both appear again, briefly, in 2007’s The Trap, which adds to the narrative the character of John Nash (famously depicted by Russell Crowe in Ron Howard’s 2001 A Beautiful Mind) and the entanglements of the discipline of psychology and game theory deployed by shadowy organizations like the RAND corporation and the CIA. This narrative is picked up again in Curtis’ most recent Can’t Get You Out of My Head, but here merely as a sidestory to an account of the rise of computing logics, which now can be traced back to George Boole in the late 19th century, the logic of which in the new film is said to have been noted by B.F. Skinner to develop behavioral analysis in the field of psychology, which gives rise to social media logics that become attractive to the countercultural expatriates of the late 1970s and wait, is that the music from 2005’s Century of the Self playing?

Aside from the at times unintelligibility of this scattershot approach, you can immediately see resonance with Foucault’s understanding of genealogy through Nietzsche not as a search for the beginning of this or that phenomena, but rather as a conceptual tool that identifies sites of emergence, descent, or “the moment of arising.” Accidents, divergence, contingency. Overlapping and contrasting temporal flows that move from past to present and back again. Genealogy, in other words,

…will never confuse itself with a quest for…”origins,” will never neglect as inaccessible the vicissitudes of history. On the contrary, it will cultivate the details and accidents that accompany every beginning; it will be scrupulously attentive to their petty malice; it will await their emergence, once unmasked, as the face of the other…(t)he genealogist needs history to dispel the chimeras of the origin…

One could look at this cast of characters above and imagine something like a supercut of Curtis’ films, stitching moments together in their historical teleology to illustrate how, say, all this nonsense on Facebook got started: well, first George Boole came up with this logic which led to…

Instead, both within the films and across his entire ouvre, Curtis seeks not to identify origins but rather draw out complex threads that at times entangle themselves with other threads, begin earlier, or later, bring in new characters, or find themselves in new spaces. “Genealogy does not pretend to go back in time to restore an unbroken continuity that operates beyond the dispersion of forgotten things,” Foucault writes, “its duty is not to demonstrate that the past actively exists in the present.” Curtis breaks this continuity regularly. At times he frustratingly will skip back in time just when the story feels like it is “getting good,” such as this moment from 2016’s Hypernormalisation, which immediately follows a segment on complexity theory and the resulting need for “politicians…to give up on any idea of trying to change the world,” to embrace the very same logics of security Foucault outlined in Security, Territory, Population, the experience of which lead to the rise of SSRIs to help cope with the psychic historical change, leading to the empowerment of the pharmaceutical industry in the 1980s. Then, a cut to this:

Hypernormalisation (Adam Curtis, 2016)

But what happened “six years earlier” in the film is not so much the origin of this part of the story, but rather an account of how Laurence Fink was led to start BlackRock after losing $100 million dollars on a faulty deal in 1986—a specific connection to the financial crises of the 1970s and the 1980s that Hypernormalisation spends its earlier moments outlining—that paved the way for a logic of security and management that was itself appropriated by the medicalization of anxiety a decade later.

What is important in Curtis’ analysis here is not to point out, say, how Big Pharma can trace its origins back to R&D by American corporations during the Second World War, or the eugenicist movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Rather, Curtis displaces the stable category of an agent like “Big Pharma” or “Herman Kahn” within a non-linear history that turns precisely on moments of accidents—what might have happened had Fink not made a faulty prediction about the trajectory of interest rates, leading him to obsess over risk management? What institutions and practices and forces were at play at the moment Fink lost this money, their logics nudging history into a different direction, logics which themselves might have emerged due to any other number of accidents at any other number of historical moments? This is far from something like a prequel or an epilogue to a story. Rather, it is an illustration of the way Curtis echoes much of Foucault’s genealogical method in his historical investigations, despite whatever similarity the target of his critique might be.

Curtis’ earlier multi-part series often weaved together discrete genealogies in each episode, the whole amounting to something like a view from above, “(descending) to seize the various perspectives, to disclose dispersions and differences, to leave things undisturbed in their own dimension and intensity.” In these earlier works, made during the long 1990s and before the widespread availability of his films on peer-to-peer networking or digital delivery platforms, Curtis’ genealogies arguably functioned as an ideal fix for any self-identified Marxist who nevertheless found something of value in Foucault’s work. In films like The Trap or even 2016’s Hypernormalisation, Curtis utilizes a genealogical approach to historical narrative alongside a lens hyperfocused on power alongside an awareness that such a thing called “ideology” indeed exists. As David Garland has argued, Foucault’s turn to genealogy emerged out of a dead-end produced by his earlier archaeological method—a realization Foucault even touches on in the conclusion of The Archaeology of Knowledge. In short: Foucault realized he could construct elaborate structures of epistemic homogeneity as a periodizing logic, systems of discourses in which what can be said and thought were governed by internal synchronic similarities even in seemingly unrelated disciplines at certain moments in time. However, he had absolutely no account for how one episteme might give way to another. Things just…changed, and a new sheriff would arrive in town called “representation” to exile the “resemblance” of the earlier period to the next town over. Genealogy here functioned as something like a solution to archaeology’s inability to account for change in what some have called its structuralist formulation.

But Foucault’s focus on epistemology and “discourse” over ideology—despite the fact that the ever-hated Louis Althusser had been making similar moves to connect the two at the same time—effectively splits the genealogical approach from a more materialist view of historical development that, I argue, Curtis effectively sutures over decades after the split first took place following the wake of 1968 and the turn away from Marxism in many corners of the left. Think of it: although not a self-identified Marxist, Curtis’ focus on the individual as something like a Jamesonian cultural logic endemic to a specific regime of political organization never comes to be the only thing thinkable in his account. Hypernormalisation gives equal measure to the 1975 New York City financial crisis as he does Patti Smith zoning out watching shop window television displays or Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (why he seems to have such disdain for women artists of the era, is, of course another question). Later, a compelling montage of 1990s Act-of-God disaster movies—Michael Bay’s Armageddon (1998), Mimi Leder’s Deep Impact (1998), and Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day (1996) and Godzilla (1998)—is stitched together before footage of 9/11, illustrating how the cultural imaginary of the 1990s seemed all but ready for an event to come and break through what Fukuyama called the “boredom” of the End of History. We are reminded, at one point, that all these films were made before 2001.

Independence Day, Deep Impact, and Godzilla in Hypernormalisation (Adam Curtis, 2016)

While clearly far from a materialist understanding of history—a common critique of Curtis is that he dabbles far too recklessly in sheer idealism—it seems clear that Curtis affords far greater purchase to something like ideology and cultural production than Foucault. Likewise, while the effect of Curtis’ longstanding political and narrative concerns might produce a helpless affect in the viewer, it is his insistence that things could be otherwise that takes from Foucault a methodological tool while leaving the baggage of defeat, totality, rules of the “thinkable and sayable” behind.

Take, for instance, Marshall Berman’s critique of Foucualt in the introduction of All That Is Solid Melts Into Air. The story Berman tells—one echoed in the work of Daniel Zamora, Alex Callinicos, and others—is that the trauma of the failure of 1968 led thinkers such as Foucault, Derrida, Lyotard, and Baudrillard to turn to what was then coming to be known as “postmodernism,” or “post-structuralism,” or whatever else one might want to call that which isn’t “materialist” or “modern.” In other words, this is where it all went wrong, where we got sidetracked and caught up in things like self-empowerment and changing “discourse,” seeing power everywhere and wanting to escape it through horizontality and the like.

To Berman, Foucault has a “savage contempt” for any project that imagines human emancipation, always already returning again and again to the way new repressive (and productive) modes of power can emerge through what otherwise sounds like progress. Foucault’s language, here, offers no freedom or even possibility for emancipation—an attractive formulation to those still grappling with the end of the sixties, as it offers

…a world-historical alibi for the sense of passivity and helplessness that gripped so many of us in the 1970s. There is no point in trying to resist the oppressions and injustices of modern life, since even our dreams of freedom only add more links to our chains; however, once we grasp the total futility of it all, at least we can relax.”

Leaving aside the sparse availability of Foucault’s 80s lectures and the later volumes of The History of Sexuality in English during Berman’s 1980s and 1990s, the critique is an interesting one. Foucault’s now heavily documented turn towards ‘technologies of the self’—and the deeply individualistic possibility of parrhesia and its revelation of a self-truth—here might both offer itself as both a rebuttal to Berman’s notion of a top-down, all encompassing philosophy that sees no outside to power and an even more troubling theory of political praxis that abandons class struggle altogether.

But curiously, this is the exact critique of the left Curtis makes, using Foucault’s genealogical method. Where Foucault’s genealogy led him to see in neoliberalism a thrilling possibility for constructing new modes of subjectivity according to Daniel Zamora’s account, Curtis sees and understands these new modes of subjectivity as part and parcel to the construction of our dystopian neoliberal present. Foucault’s wide net history sent him back to the Greeks to understand the genealogy of contemporary modes of self-governance, paradoxically burrowing his focus ever inward into the very same individual that The Order of Things famously closed denouncing. Curtis clearly understands something about this turn that even Zamora and others can only relegate to a nostalgic critique of when things were otherwise. What are we to make of this? I don’t know. Honestly, I don’t. I’m not even sure Curtis knows what he’s doing here–but perhaps most importantly–his films do. Unless the next one doesn’t. And if that’s the case then forget everything I wrote here.*

*the footnotes did not copy over from word. I don’t care enough to deal with it—if you want to see them email me.